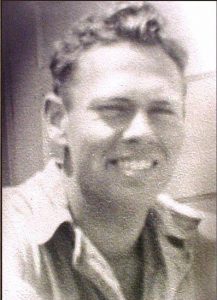

Pvt. Marvin W. Jaeger was the son of Frank W. Jaeger and Rose Brandt-Jaeger. He was born on June 1, 1918, and lived at 701 Stark Street in Wausau, Wisconsin. With his sister and brother, he attended Wausau schools and was a 1936 graduate of Wausau High School. After high school, he worked in the stockroom at Marathon Electric Motors. In April 1941, he was drafted into the U.S. Army and was inducted in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From Milwaukee, Marvin was sent to Fort Knox, Kentucky, for basic training. One of the first men he met was Ardel Schei, who he became best friends with.

The medics received hands-on training since the Army believed this was the best type of training a medic could receive. The training was done by the battalion’s medical officers since there were no classes on medical care available. There were some classes available – which appeared to have covered administrative duties – but it is not known if he attended any of the classes.

On June 14th and 16th, the battalion was divided into four detachments composed of men from different companies. Available information shows that C and D Companies, part of HQ Company and part of the Medical Detachment left on June 14, while A and B Companies, and the other halves of HQ Company and the Medical Detachment left the fort on June 16th. These were tactical maneuvers – under the command of the commanders of each of the letter companies. The three-day tactical road marches were to Harrodsburg, Kentucky, and back. Each tank company traveled with 20 tanks, 20 motorcycles, 7 armored scout cars, 5 jeeps, 12 peeps (later called jeeps), 20 large 2½ ton trucks (these carried the battalion’s garages for vehicle repair), 5, 1½ ton trucks (which included the companies’ kitchens), and 1 ambulance. The detachments traveled through Bardstown and Springfield before arriving at Harrodsburg at 2:30 P.M. where they set up their bivouac at the fairgrounds. The next morning, they moved to Herrington Lake east of Danville, where the men swam, boated, and fished. The battalion returned to Ft. Knox through Lebanon, New Haven, and Hodgenville, Kentucky. At Hodgenville, the men were allowed to visit the birthplace of Abraham Lincoln. The purpose of the maneuvers was to give the men practice at loading, unloading, and setting up administrative camps to prepare them for the Louisiana maneuvers.

At the end of the month, the battalion found itself at the firing range and appeared to have spent the last week there. According to available information, they were there from 4:00 A.M. until 8:30 A.M. when they left the range. They then had to clean the guns which took them until 10:30 A.M. One of the complaints they had about the firing range was that it was so hot and humid that when they got back from it their clothes felt like they had stood out in the rain. Right after July 4th, the battalion went on a nine-day maneuver.

Congress on August 13, 1941, extended the time that federalized National Guard units serving in the regular army would serve by 18 months. The 192nd Tank Battalion was sent to Louisiana, in the late summer of 1941, to take part in maneuvers. About half of the battalion left Ft. Knox on September 1st in trucks and other wheeled vehicles and spent the night in Clarksville, Tennessee, where they spent the night. By 7:00 A.M. the next morning, the detachment was on the move.

On the second day, the soldiers saw their first cotton fields which they found fascinating. They spent the night in Brownsville, Tennessee, and were again on the move the following morning at 7:00 A.M. At noon, the convoy crossed the Mississippi River which they found amazing, and spent the night in Clarksdale, Mississippi. At noon the next day, the convoy crossed the lower part of Arkansas and arrived at Tallulah, Louisiana, where, they washed, relaxed, and played baseball against the locals. It also gave them a break from sitting on wooden benches in the trucks. The remaining soldiers, the tanks, and other equipment were sent by train and left the base on September 3rd. When they arrived at Tremont, Lousiana, the men, and trucks who had driven to Louisiana were waiting for them at the train station.

The battalion was assigned to the Red Army, attached to the Fourth Cavalry, and stationed at Camp Robinson, Arkansas. Two days later it made a two-day move, as a neutral unit, to Ragley, Louisiana, and was assigned to the Blue Army under the command of Gen George S. Patton. The battalion’s bivouac was in the Kisatchi Forest where the soldiers dealt with mosquitoes, snakes, wood ticks, snakes, and alligators.

During the maneuvers, tanks held defensive positions and usually were held in reserve by the higher headquarters. For the first time, the tanks were used to counter-attack, in support of infantry, and held defensive positions. Some men felt that the tanks were finally being used like they should be used and not as “mobile pillboxes.” The maneuvers were described by other men as being awakened at 4:30 A.M. and sent to an area to engage an imaginary enemy. After engaging the enemy, the tanks withdrew to another area. The crews had no idea what they were doing most of the time because they were never told anything by the higher-ups. A number of men felt that they just rode around in their tanks a lot.

While training at Ft. Knox, the tankers were taught that they should never attack an anti-tank gun head-on. One day during the maneuvers, their commanding general threw away the entire battalion doing just that. After sitting out a period of time, the battalion resumed the maneuvers. The major problem for the tanks was the sandy soil. On several occasions, tanks were parked and the crews walked away from them. When they returned, the tanks had sunk into the sandy soil up to their hauls. To get them out, other tanks were brought in and attempted to pull them out. If that didn’t work, the tankers brought a tank wrecker from Camp Polk to pull the tank out of the ground.

It was not uncommon for the tankers to receive orders to move at night. On October 2nd at 2:30 A.M., they were awakened by the sound of a whistle which meant they had to get the tanks ready to move. Those assigned to other duties loaded trucks with equipment. Once they had assembled into formations, they received the order to move, without headlights, to make a surprise attack on the Red Army. By 5:30 that morning – after traveling 40 miles in 2½ hours from their original bivouac in the dark – they had established a new bivouac and set up their equipment. They camouflaged their tanks and trucks and set up sentries to look for paratroopers or enemy troops. At 11:30, they received orders, and 80 tanks and armored vehicles moved out into enemy territory. They engaged the enemy at 2:38 in the afternoon and an umpire with a white flag determined who was awarded points or penalized. At 7:30 P.M., the battle was over and the tanks limped back to the bivouac where they were fueled and oiled for the next day.

The one good thing that came out of the maneuvers was that the tank crews learned how to move at night. At Ft. Knox this was never done. Without knowing it, the night movements were preparing them for what they would do in the Philippines since most of the battalion’s movements there were made at night. The drivers learned how to drive at night and to take instructions from their tank commanders who had a better view from the turret. A number of motorcycle riders from other tank units were killed because they were riding their bikes without their headlights on which meant they could not see obstacles in front of their bikes. When they hit something they fell to the ground and the tanks following them went over them. This happened several times before the motorcycle riders were ordered to turn on their headlights.

He and the other medics dealt with snake bites which were also a problem and at some point, it seemed that every other man in the battalion was bitten by a snake. The platoon commanders carried a snake bite kit that was used to create a vacuum to suck the poison out of the bite. The bites were the result of the night cooling down and snakes crawling under the soldiers’ bedrolls for warmth while the soldiers were sleeping on them.

There was one multicolored snake – about eight inches long – that was beautiful to look at, but if it bit a man he was dead. The good thing was that these snakes would not just strike at the man but only strike if the man forced himself on it. When the soldiers woke up in the morning they would carefully pick up their bedrolls to see if there were any snakes under them. To avoid being bitten, men slept on the two-and-a-half-ton trucks or on or in the tanks. Another trick the soldiers learned was to dig a small trench around their tents and lay rope in the trench. The burs on the rope kept the snakes from entering the tents. The snakes were not a problem if the night was warm. They also had a problem with the wild hogs in the area. In the middle of the night while the men were sleeping in their tents they would suddenly hear hogs squealing. The hogs would run into the tents pushing on them until they took them down and dragged them away.

They also had a problem with the wild hogs in the area. In the middle of the night while the men were sleeping in their tents they would suddenly hear hogs squealing. The hogs would run into the tents pushing on them until they took them down and dragged them away.

The food was also not very good since the air was always damp which made it hard to get a fire started. Many of their meals were C ration meals of beans or chili that they choked down. Washing clothes was done when the men had a chance. They did this by finding a creek, looking for alligators, and if there were none, taking a bar of soap and scrubbing whatever they were washing. Clothes were usually washed once a week or once every two weeks.

On one occasion, members of the detachment were receiving lunch when someone yelled, “Gas!” A number of the medics climbed into a duce and a half truck and laid down on the floor of its bed to hide from the umpires. They thought they were safe when the truck tipped a little and the major looked in the truck and yelled at them to get out of it. The umpires wrote “gas casualty” on their foreheads. They were taken to the hospital and for the next two days, they were carried around on stretchers. Many of the men thought it was the best two days of the maneuvers.

After the maneuvers, the battalion members expected to return to Ft. Knox but received orders to report to Camp Polk, Louisiana. It was on the side of a hill the battalion learned that they had been selected to go overseas. Those men who were married with dependents, who were 29 years old or older. or whose enlistments in the National Guard were about to end while the battalion was overseas were allowed to resign from federal service. Officers too old for their ranks also were released. This included the 192nd’s commanding officer. They were replaced with men from the 753rd Tank Battalion who volunteered or had their names drawn from a hat. Both new and old members of the battalion were given furloughs home to say their goodbyes. When they returned to Camp Polk and prepared for duty overseas by putting cosmoline on anything that would rust.

The battalion was scheduled to receive brand new M3 tanks but for some unknown reason, the tanks were not available. Instead, the battalion received tanks from the 753rd Tank Battalion and the 3rd Armor Division. The tanks were only new to the 192nd since many of these tanks were within 5 hours of their required 100-hour required maintenance. Peeps – later called Jeeps – were also given to the battalion, and the battalion’s half-tracks which replaced their reconnaissance cars were waiting for them in the Philippines.

The decision to send the battalion overseas appeared to have been made well before the maneuvers. According to one story, the decision for this move – which had been made on August 13, 1941 – was the result of an event that took place in the summer of 1941. A squadron of American fighters was flying over Lingayen Gulf, in the Philippines, when one of the pilots, who was flying at a lower altitude than the other planes, noticed something odd. He took his plane down, identified a flagged buoy in the water, and saw another in the distance. Following the buoys, he came upon more buoys that lined up, in a straight line for 30 miles to the northwest, in the direction of Formosa which had a large radio transmitter used by the Japanese military. The squadron continued its flight plan south to Mariveles and returned to Clark Field. When the planes landed, it was too late to do anything that day.

The next day, when another squadron was sent to the area, the buoys had been picked up by a fishing boat – with a tarp on its deck covering the buoys – which was seen making its way to shore. Since communication between the Air Corps and the Navy was difficult, the boat escaped. According to this story, it was at that time the decision was made to build up the American military presence in the Philippines.

Many of the original men believed that the reason they were selected to be sent overseas was that they had performed well on the maneuvers. The story was that they were personally selected by General George S. Patton – who had commanded their tanks and the tanks of the 191st Tank Battalion during the maneuvers s the First Tank Group – during the maneuvers. Patton did praise the tank battalions for their performance during the maneuvers, but there is no evidence he had anything to do with them going overseas.

The fact was that the battalion was part of the First Tank Group which was headquartered at Ft. Knox and operational by June 1941. Two members of the battalion – one from Illinois and the other from Ohio – both wrote about the First Tank Group in January 1941 newspaper columns written for their local newspapers. One man identified every tank battalion in the tank group. During the maneuvers, they even participated as the First Tank Group. The tank group was made up of the 70th and 191st Tank Battalions – the 191st had been a National Guard medium tank battalion while the 70th was a Regular Army medium tank battalion – at Ft. Meade, Maryland. The 193rd was at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and the 194th was at Ft. Lewis, Washington. The 192nd, 193rd, and 194th had been National Guard light tank battalions. It is known that the military presence in the Philippines was being built up at the time, and documents show that the entire tank group had been scheduled to be sent to the Philippines long before August 13th. The buoys being spotted by the pilot may have sped up the transfer of the tank battalions to the Philippines, with only the 192nd and 194th reaching the islands, but it was not the reason the tank battalions were sent there. It is known that the 193rd was on its way to the Philippines when Pearl Harbor was attacked and the battalion was held in Hawaii after arriving there. One of the two medium tank battalions – most likely the 191st – had 48-hour standby orders for the Philippines which were canceled on December 10th.

HQ Company left for the West Coast a few days earlier than the rest of the 192nd to make preparations for the battalion. At 8:30 A.M. on October 20th, over at least three train routes, the companies were sent to San Francisco, California. Most of the soldiers of each company rode on one train that was followed by a second train that carried the company’s tanks. At the end of the second train was a boxcar, with equipment and spare parts, followed by a passenger car that carried soldiers. HQ Company and A Company took the southern route, B Company went west through the middle of the country, and A Company went north then west along the Canadian border. When they arrived in San Francisco, they were ferried, by the U.S.A.T. General Frank M. Coxe, to Ft. McDowell on Angel Island.

After the maneuvers, the battalion members expected to return to Ft. Knox but received orders to report to Camp Polk, Louisiana. It was on the side of a hill the battalion learned that they had been selected to go overseas. Those men who were married with dependents, who were 29 years old or older. or whose enlistments in the National Guard were about to end while the battalion was overseas were allowed to resign from federal service. Officers too old for their ranks also were released. This included the 192nd’s commanding officer. They were replaced with men from the 753rd Tank Battalion who volunteered or had their names drawn from a hat. Both new and old battalion members were given ten-day furloughs home to say their goodbyes. When they returned to Camp Polk and prepared for duty overseas by putting cosmoline on anything that would rust.

The battalion was scheduled to receive brand new M3 tanks but for some unknown reason, the tanks were not available. Instead, the battalion received tanks from the 753rd Tank Battalion and the 3rd Armor Division. The tanks were only new to the 192nd since many of these tanks were within 5 hours of their required 100-hour required maintenance. Peeps – later called Jeeps – were also given to the battalion, and the battalion’s half-tracks which replaced their reconnaissance cars were waiting for them in the Philippines.

The decision to send the battalion overseas appeared to have been made well before the maneuvers. According to one story, the decision for this move – which had been made on August 13, 1941 – was the result of an event that took place in the summer of 1941. A squadron of American fighters was flying over Lingayen Gulf, in the Philippines, when one of the pilots, who was flying at a lower altitude than the other planes, noticed something odd. He took his plane down, identified a flagged buoy in the water, and saw another in the distance. Following the buoys, he came upon more buoys that lined up, in a straight line for 30 miles to the northwest, in the direction of Formosa which had a large radio transmitter used by the Japanese military. The squadron continued its flight plan south to Mariveles and returned to Clark Field. When the planes landed, it was too late to do anything that day.

The next day, when another squadron was sent to the area, the buoys had been picked up by a fishing boat – with a tarp on its deck covering the buoys – which was seen making its way to shore. Since communication between the Air Corps and the Navy was difficult, the boat escaped. According to this story, it was at that time the decision was made to build up the American military presence in the Philippines.

Many of the original men believed that the reason they were selected to be sent overseas was that they had performed well on the maneuvers. The story was that they were personally selected by General George S. Patton – who had commanded their tanks and the tanks of the 191st Tank Battalion during the maneuvers s the First Tank Group – during the maneuvers. Patton did praise the tank battalions for their performance during the maneuvers, but there is no evidence he had anything to do with them going overseas.

The fact was that the battalion was part of the First Tank Group which was headquartered at Ft. Knox and operational by June 1941. Two members of the battalion – one from Illinois and the other from Ohio – both wrote about the First Tank Group in January 1941 newspaper columns written for their local newspapers. One man identified every tank battalion in the tank group. During the maneuvers, they even participated as the First Tank Group. The tank group was made up of the 70th and 191st Tank Battalions – the 191st had been a National Guard medium tank battalion while the 70th was a Regular Army medium tank battalion – at Ft. Meade, Maryland. The 193rd was at Ft. Benning, Georgia, and the 194th was at Ft. Lewis, Washington. The 192nd, 193rd, and 194th had been National Guard light tank battalions. It is known that the military presence in the Philippines was being built up at the time, and documents show that the entire tank group had been scheduled to be sent to the Philippines long before August 13th. The buoys being spotted by the pilot may have sped up the transfer of the tank battalions to the Philippines, with only the 192nd and 194th reaching the islands, but it was not the reason the tank battalions were sent there. It is known that the 193rd was on its way to the Philippines when Pearl Harbor was attacked and the battalion was held in Hawaii after arriving there. One of the two medium tank battalions – most likely the 191st – had 48-hour standby orders for the Philippines which were canceled on December 10th.

HQ Company and the Medical Detachment left for the West Coast a few days earlier than the rest of the 192nd to make preparations for the battalion. At 8:30 A.M. on October 20th, over at least three train routes, the companies were sent to San Francisco, California. Most of the soldiers of each company rode on one train that was followed by a second train that carried the company’s tanks. At the end of the second train was a boxcar, with equipment and spare parts, followed by a passenger car that carried soldiers. HQ Company, the Medical Detachment, and A Company took the southern route, B Company went west through the middle of the country, C Company went through the center of the country a bit further north than B Company and D Company went north then west along the Canadian border. When they arrived in San Francisco, they were ferried, by the U.S.A.T. General Frank M. Coxe, to Ft. McDowell on Angel Island.

On the island, Marvin was involved in giving physicals to the members of the battalion. Men found to have minor health issues were held back and scheduled to rejoin the battalion at a later date. Other men were simply replaced with men who had been sent to the island as replacements. It is known that the 757th Tank Battalion was at Ft. Ord, California, and that men from the battalion joined the 192nd to replace men who failed their final physicals. It was also at this time that Col. James R. N. Weaver became the commanding officer of the 192nd.

When they arrived at Guam on Sunday, November 16th, the ships took on water, bananas, coconuts, and vegetables. Although they were not allowed off the ship, the soldiers were able to mail letters home before sailing for Manila the next day. At one point, the ships passed an island at night and did so in total blackout. This for many of the soldiers was a sign that they were being sent into harm’s way. The blackout was strictly enforced and men caught smoking on deck after dark spent time in the ship’s brig. Three days after leaving Guam the men spotted the first islands of the Philippines. The ships sailed around the south end of Luzon and then north up the west coast of Luzon toward Manila Bay.

The ships entered Manila Bay, at 8:00 A.M., on Thursday, November 20th, and docked at Pier 7 later that morning. One thing that was different about their arrival was that instead of a band and a welcoming committee waiting at the pier to tell them to enjoy their stay in the Philippines and see as much of the island as they could, a party came aboard the ship – carrying guns – and told the soldiers, “Draw your firearms immediately; we’re under alert. We expect a war with Japan at any moment. Your destination is Fort Stotsenburg, Clark Field.” At 3:00 P.M., as the enlisted men left the ship, a Marine was checking off their names. When an enlisted man said his name, the Marine responded with, “Hello sucker.” Those who drove trucks drove them to the fort, while the maintenance section remained behind at the pier to unload the tanks. Some men stated they rode a train to Ft. Stotsenberg while other men stated they rode busses to the base.

On Monday, December 1st, the tanks were ordered to the perimeter of Clark Field to guard against paratroopers. The 194th guarded the northern end of the airfield, while the 192nd guarded the southern end where the two runways came together and formed a V. Two members of every tank crew remained with their tanks at all times, and meals were brought to them by food trucks. On Sunday, December 7th, the tankers spent a great deal of the day loading bullets into machine gun belts and putting live shells for the tanks’ main guns into the tanks.

Gen. Weaver on December 2nd ordered the tank group to full alert. According to Capt. Alvin Poweleit, Weaver appeared to be the only officer on the base interested in protecting his unit. When Poweleit suggested they dig air raid shelters – since their bivouac was so near the airfield – the other officers laughed. He ordered his medics to dig shelters near the tents of the companies they were with and at the medical detachment’s headquarters. On December 3rd the tank group officers had a meeting with Gen Weaver on German tank tactics. Many believed that they should be learning how the Japanese used tanks. That evening when they met Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, they concluded that he had no idea how to use tanks. It was said they were glad Weaver was their commanding officer. That night the airfield was in complete black-out and searchlights scanned the sky for enemy planes. All leaves were canceled on December 6th.

It was the men manning the radios in the 192nd communications tent who were the first to learn – at 2 a.m. – of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 8th. Major Ted Wickord, Gen. James Weaver, and Major Ernest Miller, 194th, and Capt. Richard Kadel, 17th Ordnance read the messages of the attack. At one point, even Gen. King came to the tent to read the messages. The officers of the 192nd were called to the tent and informed of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The 192nd’s company commanders were called to the tent and told of the Japanese attack.

Most of the tankers heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor at roll call that morning. Some men believed that it was the start of the maneuvers they were expecting to take part in. They were also informed that their barracks were almost ready and that they would be moving into them shortly. News reached the tankers that Camp John Hay had been bombed at 9:00 a.m.

The medics had just had lunch and were in their tents taking naps. It was just after noon and the men were listening to Tokyo Rose who announced that Clark Field had been bombed. They got a good laugh out of it since they hadn’t seen an enemy plane all morning, but before the broadcast ended that had changed. At 12:45 p.m., they heard the sound of planes, since the sides of their tents were up for ventilation, men looked up at the formation of planes in the distance. Men commented about how beautiful the formation was, while other men commented that the planes must be American Navy planes; that was until someone saw Red Dots on the wings. They then saw what looked like “raindrops” falling from the planes and when bombs began exploding on the runways they knew the planes were Japanese. It was stated they took cover, but the planes were bombing Clark Field and not where they bivouacked. It was stated that no sooner had one wave of planes finished bombing and were returning to Formosa than another wave came in and bombed. The second wave was followed by a third wave of bombers. One member of the 192nd, Robert Brooks, D Co., was killed during the attack.

The bombers were quickly followed by Japanese fighters which sounded like angry bees as they strafed the airfield. The medics watched as American pilots attempted to get their planes off the ground. As they roared down the runway, Japanese fighters strafed the planes causing them to swerve, crash, and burn. Only one P-40 got off the ground. Those that did get airborne were barely off the ground when they were hit. The planes exploded and crashed to the ground tumbling down the runways. The Japanese planes were as low as 50 feet above the ground and the pilots would lean out of the cockpits so they could more accurately pick out targets to strafe. The tankers said they saw the pilots’ scarfs flapping in the wind. One tanker stated that a man with a shotgun could have shot a plane down.

The Coast Artillery had trained with the latest anti-aircraft guns while in the States, but the decision was made to send them to the Philippines with older guns. They also had proximity fuses for the shells and had to use an obsolete method to cut the fuses. This meant that most of their shells exploded harmlessly in the air.

The Zeros strafed the airfield and headed toward and turned around behind Mount Arayat. One tanker stated that the planes were so low that a man with a shotgun could have shot a plane down. It was also stated that the tankers could see the scarfs of the pilots flapping in the wind as they looked for targets to strafe. Having seen what the Japanese were doing, the battalion’s half-tracks were ordered to the base’s golf course which was at the opposite end of the runways. There they waited for the Zeros to complete their flight pattern. The first six planes that came down the length of the runways were hit by fire from the half-tracks. As the planes flew over the golf course, flames and smoke were seen trailing behind them. When the other Japanese pilots saw what happened, they pulled up to about 3,000 feet before dropping their small incendiary bombs and leaving. The planes never strafed the airfield again.

While the attack was going on, the Filipinos who were building the 192nd’s barracks took cover. After the attack, they went right back to work on building the barracks. This happened several times during the following air raids until the barracks were destroyed by bombs during an air raid. According to the members of the battalion, it appeared the Filipino contractor really wanted to be paid; war or no war.

Capt. Alvin Poweleit and an unknown number of medics drove to the airfield to see if they could aid the wounded and dying. When they got there, the hangers and barracks were destroyed, and the B-17s also were totally wrecked. As they were doing this, Japanese fighters began strafing the airfield. To avoid being hit, they hid in a bomb crater. After the planes were gone, the medics treated Filipino Lavenderos (women who did laundry) and a number of houseboys. They also treated officers and enlisted men and saw the dead, men with half their heads torn off, men with their intestines lying on the ground, and men with their backs blown out.

When the Japanese were finished, there was not much left of the airfield. The soldiers watched as the dead, dying, and wounded were hauled to the hospital on bomb racks, and trucks, and anything else that could carry the wounded was in use. Within an hour the hospital had filled to capacity. As the tankers watched the medics placed the wounded under the building. Many of these men had their arms and legs missing. When the hospital ran out of room for the wounded, the members of the tank battalions set up cots under mango trees for the wounded and even the dentist gave medical aid to the wounded. The medical detachment was moved to an open field where the medics were ordered by Capt. Poweleit to dig a large foxhole. The foxhole became their new quarters.

The next morning the decision was made to move the battalion’s headquarters into a tree-covered area. Those men not assigned to a tank or half-track walked around Clark Field to look at the damage. As they walked, they saw there were hundreds of dead. Some were pilots who had been caught asleep, because they had flown night missions, in their tents during the first attack. Others were pilots who had been killed attempting to get to their planes. The tanks were still at the southern end of the airfield when a second air raid took place on the 10th. This time the bombs fell among the tanks of the battalion at the southern end of the airfield wounding some men.

C Company was ordered to the area of Mount Arayat on December 9th. Reports had been received that the Japanese had landed paratroopers in the area. No paratroopers were found, but it was possible that the pilots of damaged Japanese planes may have jumped from them. That night, they heard bombers fly at 3:00 a.m. on their way to bomb Nichols Field. The battalion’s tanks were still bivouacked among the trees when a second air raid took place on the 10th. This time the bombs fell among the tanks of the battalion at the southern end of the airfield wounding some men. The Japanese landed troops at Aparri on the 10th and Legaspi on the 11th.

B Company was sent to the Barrio of Dau on December 12th so it could protect a highway bridge and railroad bridge against sabotage. At about 8:30 a.m. the elements of the battalion still at Clark Field lived through another attack. Since it was overcast, the bombers came in low and dropped their bombs which in many cases did not explode. 2nd Lt Albert Bartz, A Co., had been wounded in his shoulder and had a broken clavicle. That night the 194th was sent to Calumpit Bridge. Since the bombing was so close to where they were bivouacked, HQ Company and the medical detachment – which was attached to HQ Company – moved to a gravel pit and set up operations. If a bomb had landed near them the sand and gravel would have collapsed on them.

Around December 15th, after the Provisional Tank Group Headquarters was moved to Manila, Major Maynard Snell, a 192nd staff officer, stopped at Ft. Stotsenburg where anything that could be used by the Japanese was being destroyed. He stopped the destruction long enough to get five-gallon cans loaded with high-octane gasoline and small arms ammunition put onto trucks to be used by the tanks and infantry. The medical detachment on the 18th spent its time treating tankers who had contracted gonorrhea and others for syphilis. The men were able to send home radiograms on the 20th. The 192nd received orders to proceed north at 3 a.m. on the 21st. They were told that the Japanese did not have any heavy guns onshore. As it turned out, they were well-equipped.

On December 22nd, a platoon of tanks from B Company engaged Japanese tanks in the first tank battle of World War II involving American tanks. The tank platoon commander’s tank was disabled and the crew was captured by the Japanese. Another tank had an armor-piercing shell go through its turret. The tank commander survived because he had just bent over to talk to his driver moments before the shell hit the tank. A shell hit a third tank in its machine gun’s bow port and the concussion came in through the port and decapitated the gunner. The tank’s driver was covered in his blood. The tanks withdrew from the area. The remaining tanks withdrew through an area where a battle between the Japanese and the Philippine Scouts had taken place. It was stated there were dead horses, bodies, and body parts everywhere they looked. The tank group remained in Manila until December 23rd when it moved with the 194th north out of Manila.

The medical detachment was at Sison on the 23rd and was shelled and bombed. The medics left their trucks and ambulances and took cover. An officer came up to them and said to them that none of the shells were close to them. It was his first day under fire. A shell exploded in a tree top and took off his head. The detachment did not get the order to withdraw and soon found itself behind enemy lines. They made their way south and drove through the barrio of Urdaneta. When they went through, the barrio was on fire. On December 25th, they were south of Rosales and set up their aid station. The medics also checked up on the different companies which at times included tank companies from the 194th. Capt. Walter Write., A Co., was killed on the 26th. They remained there until the 27th when they moved to Santo Tomas. While there they were shelled and treated for minor wounds. General Douglas MacArthur on December 28th, ordered that medics should not carry guns. The officers and enlisted men of the medical detachment ignored the order.

The detachment was at Santo Tomas on December 28th and went through three hours of shelling. A few minor injuries were reported. The medics were ordered by Gen. MacArthur not to carry guns. On that same date, Capt. Alvin Poweleit, Sgt. Howard Massey, and Cpl. John Reynolds and PFC Curis Massey encountered a Japanese patrol. The three soldiers were in a streambed when they heard a twig snap. Carefully, they made their way back to their truck and hid in the brush. As they watched, a Japanese patrol made its way down the bed of the stream. Each of the medical detachment men aimed their guns at a specific member of the patrol. They opened fire and continued to fire until the patrol was wiped out. The battalion was ordered to fall back to San Isidro which was located south of Cabanatuan where they were shelled again resulting in one tank being flipped onto its side when a shell landed near it. The crew was taken to a field hospital with minor injuries, and the tank was uprighted and put back into use with a replacement crew. It was noted that the tank crews were physically in poor condition from lack of sleep, lack of food, and constantly being on alert.

The next morning, December 30th, 2nd Lt. William Read’s tank platoon was serving as a rearguard and was in a dry rice paddy when it came under enemy fire by Japanese mortars. Read was riding in a tank when one of the enemy rounds hit one of its tracks knocking it out. After escaping the tank, Read stood in front of it and attempted to free the crew. A second round hit the tank, directly below where he was standing blowing off his legs at the knees and leaving him mortally wounded. The other members of his crew carried Read from the tank and laid him under a bridge. Read would not allow himself to be evacuated since there were other wounded soldiers. He insisted that these men be taken first. He would die in the arms of Pvt. Ray Underwood as the Japanese overran the area.

The Japanese had broken through two Philippine Divisions holding Route 5 and C Company was ordered to Baluiag to stop the advance so that the remaining forces could withdraw. On the morning of December 31st, 1st Lt. William Gentry, commanding officer of a platoon of C Company tanks, sent out reconnaissance patrols north of the town of Baluiag. The patrols ran into Japanese patrols, which told the Americans that the Japanese were on their way. Knowing that the railroad bridge was the only way to cross the river into the town, Gentry set up his defenses in view of the bridge and the rice patty it crossed. One platoon of tanks under the command of 2nd Lt. Marshall Kennady was to the southeast of the bridge, while Gentry’s tanks were to the south of the bridge hidden in huts in the barrio. The third platoon commanded by Capt Harold Collins was to the south on the road leading out of Baluiag, and 2nd Lt. Everett Preston had been sent south to find a bridge to cross to attack the Japanese from behind.

Early on the morning of the 31st, the Japanese began moving troops across the bridge. The engineers came next and put down planking for tanks. A little before noon Japanese tanks began crossing the bridge. Later that day, the Japanese assembled a large number of troops in the rice field on the northern edge of the town.

Major John Morley, of the Provisional Tank Group, came riding in his jeep into Baluiag. He stopped in front of a hut and was spotted by the Japanese who had lookouts on the town’s church steeple. The guard became very excited so Morley, not wanting to give away the tanks’ positions, got into his jeep and drove off. Gentry had told Morley that his tanks would hold their fire until he was safely out of the village. When Gentry felt the Morley was out of danger, he ordered his tanks to open up on the Japanese tanks at the end of the bridge. The tanks then came smashing through the huts’ walls and drove the Japanese in the direction of Lt. Marshall Kennady’s tanks. Kennady had been radioed and was waiting. Kennady held his fire until the Japanese were in view of his platoon and then joined in the hunt. The Americans chased the tanks up and down the streets of the village, through buildings and under them. By the time C Company was ordered to disengage from the enemy, they had knocked out at least eight enemy tanks.

C Company withdrew to Calumpit Bridge after receiving orders from Provisional Tank Group. When they reached the bridge, they discovered it had been blown. Finding a crossing the tankers made it to the south side of the river. Knowing that the Japanese were close behind, the Americans took their positions in a harvested rice field and aimed their guns to fire a tracer shell through the harvested rice. This would cause the rice to ignite which would light the enemy troops. The tanks were about 100 yards apart. The Japanese crossing the river knew that the Americans were there because the tankers shouted at each other to make the Japanese believe troops were in front of them. The Japanese were within a few yards of the tanks when the tanks opened fire which caused the rice stacks to catch fire. The fighting was such a rout that the tankers were using a 37 mm shell to kill one Japanese soldier.

The tank company was next sent to the Barrio of Porac to aid the Philippine Army which was having trouble with Japanese artillery fire. From a Filipino lieutenant, they learned where the guns were located and attacked destroying three of the guns and chasing the Japanese destroying trucks, and killing the infantry. The tanks were ordered to fall back to San Fernando and were refueled and received ammunition.

On January 1st, conflicting orders, about who was in command, were received by the defenders who were attempting to stop the Japanese advance down Route 5 which would allow the Southern Luzon Forces to withdraw toward Bataan. General Wainwright was unaware of the orders since they came from Gen. MacArthur’s chief of staff. Because of the orders, there was confusion among the Filipinos and American forces defending the bridge over the Pampanga River with half of the defenders withdrawing. Due to the efforts of the Self-Propelled Mounts, the 71st Field Artillery, and a frenzied attack by the 192nd Tank Battalion the Japanese were halted and the Southern Luzon Forces crossed the bridge.

On the top of a hill, the medics watched the 31st Infantry halt the Japanese advance with their Garand rifles. The trees had been stripped of vegetation because of the artillery fire. The medics dropped back to the Pilar-Bagac Road. Gen Douglas MacArthur visited the area on the 7th and commented that the soldiers he saw should be in the hospital. Capt. Alvin Poweleit asked him, “Who’d man the tanks?” MacArthur shook his head and walked away.

It was at this time the tank battalions received these orders which came from Gen. Weaver: “Tanks will execute maximum delay, staying in position and firing at visible enemy until further delay will jeopardize withdrawal. If a tank is immobilized, it will be fought until the close approach of the enemy, then destroyed; the crew previously taking positions outside and continuing to fight with the salvaged and personal weapons. Considerations of personal safety and expediency will not interfere with accomplishing the greatest possible delay.”

From January 2nd to 4th, the 192nd held the road open from San Fernando to Dinalupihan so the Southern forces could escape. The medics were at Culis on January 4th where they treated many of the 194th Tank Battalion’s wounded. When a Japanese plane came in very low to straf, it was hit by machine gun fire from a tank and crashed three or four miles away from where it was hit. The tankers were given a rest on the 6th. They were half-dead, half-fed, and half wore uniforms that were ragged. Most of the tank crew members were wounded in some way.

At 2:30 A.M., on January 6th, the Japanese attacked Remedios in force using smoke which was an attempt by the Japanese to destroy the tank battalions. The smoke blew back into the Japanese and since they were wearing white shirts, they were lit by the moonlight. After taking heavy casualties they withdrew. That night, the tank battalions were covering the withdrawal of all troops around Hermosa. The 194th crossed the bridge covered by the 192nd and then covered the 192nd’s crossing of the bridge before it was destroyed by the engineers. The 192nd was the last unit to enter Bataan.

The next day, the battalion was between Culo and Hermosa and assigned a road to enter Bataan which was worse than having no road. The half-tracks kept throwing their rubber tracks and the members of the 17th Ordnance Company assigned to each battalion had to re-track them in dangerous situations. After daylight, Japanese artillery fire was landing all around the tanks.

The medics were at kilometer 142 on January 12th and fell back to Pilar and Balanga on January 18th. The medics had a hard time sleeping because of the fear of Japanese snipers. The next day they dropped back to Orion and dropped back to kilometer 147 the next day. That afternoon the soldiers caught a pig and roasted it. The chow truck arrived at 6:00 p.m. and they ate their first “American” food in two days. The tanks on the 20th stopped a Japanese landing. The Japanese landed troops on a point protruding from the main peninsula of Bataan on the 23rd. The troops were quickly cut off, and when an attempt was made to reinforce them, the Japanese landed the troops on another point. It was noted that they were bombed and strafed repeatedly and that they were not fed.

On the 28th, Capt. Alvin Poweleit, Sgt. Howard Massey, Pvt. Curtis Massey, and Cpl. John Reynolds were making the rounds to the battalion’s aid stations in an ambulance. As night was falling, they came under heavy fire from Japanese artillery. To get out of the line of fire, they pulled off the road and camouflaged the ambulance. Sgt. Massey went down a slope to the bed of a creek. While there, he heard the sound of twigs cracking. He ran to the ambulance and told the other soldiers what he had heard, and each man gave his opinion of the situation. Believing that the noise was caused by the Japanese, the medics readied their guns. As medics, they were not supposed to be carrying since they were medics. Soon they saw eight camouflaged Japanese soldiers approaching. Sgt. Massey planned the method of attack. Capt. Poweleit would take the first man, Sgt. Massey would take the second, Cpl. Reynolds the third man, and Pvt. Massey took the fourth man. They would do the same with the remaining Japanese soldiers. The four men opened fire and wiped out the patrol. Knowing that more Japanese were in the area, they got in the ambulance and out of the area as fast as they could.

The medical detachment set up its aid station in thickets and hid it under trees. Since they were constantly falling back, they did this on almost a daily basis.

The battalions took on the job of guarding the airfields in Bataan in February which had been constructed because of the belief that aid would be coming by air. Throughout the Battle of Bataan, men held the belief that aid would arrive. The Japanese bombed the airfields during the day and at night the engineers would repair them. 50-gallon drums were placed around the airfields to mark the runways, and at night fires could be lit in them to outline the landing strip. The well-camouflaged tanks surrounded the airfield and had several plans on how they would defend the airfields from paratroopers.

After being up all night on beach duty, B Company, on February 3rd, was strafed by Japanese planes after one of its members pulled his half-track from under the jungle canopy, onto the beach, took a pot-shot at Recon Con Joe, and missed. Recon Joe was attempting to locate the tanks. Twenty minutes later Japanese planes appeared and dropped bombs on the company that exploded in the tree tops. Two men were killed in the attack and two others later died of their wounds.

The 192nd took part in the Battle of the Points on the west coast of Bataan. The Japanese landed troops on points sticking out of Bataan but they ended up trapped. When reinforcements were landed, they landed in the wrong places. One battle was the Lapay-Longoskawayan points from January 23rd to 29th, a second battle was the Quinawan-Aglaloma points from January 22nd to February 8th, and the last battle was the Sililam-Anyasan points from January 27th to February 13th. The defenders successfully eliminated the points by driving their tanks along the Japanese defensive line and firing their machine guns. The 45th Infantry, Philippine Scouts followed the tanks eliminating any resistance and driving the Japanese Marines over the edge of the cliffs where they hid in caves. The tanks fired into the caves killing or forcing them out of them into the sea.

C Company was ordered to Quinauan Point where the Japanese had landed troops. The tanks arrived about 5:15 P.M. He did a quick reconnaissance of the area, and after meeting with the commanding infantry officer, made the decision to drive tanks into the edge of the Japanese position and spray the area with machine-gun fire. The progress was slow but steady until a Japanese .37 milometer gun was spotted in front of the lead tank, and the tanks withdrew. It turned out that the gun had been disabled by mortar fire, but the tanks did not know this at the time. The decision was made to resume the attack the next morning, so the 45th Infantry dug in for the night.

The next day, another platoon did reconnaissance before pulling into the front line. They repeated the maneuver and sprayed the area with machine gunfire. As they moved forward, members of the 45th Infantry followed the tanks. The troops made progress all day long along the left side of the line. The major problem the tanks had to deal with was tree stumps which they had to avoid so they would not get hung up on them. The stumps also made it hard for the tanks to maneuver. Coordinating the attack with the infantry was difficult, so the decision was made to bring in a radio car so that the tanks and infantry could talk with each other.

On February 4th, at 8:30 A.M. five tanks and the radio car arrived. The tanks were assigned the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, so each tank commander knew which tank was receiving an order. Each tank also received a walkie-talkie, as well as the radio car and infantry commanders. This was done so that the crews could coordinate the attack with the infantry and so that each tank could be ordered to where it was needed. John led as many as five attacks a day, into the pocket, to wipe out the Japanese. A few of the cleansing missions lasted for five hours. After several days of this, the pocket was completely cleared of enemy soldiers. The Japanese were pushed back almost to the cliffs when the attack was halted for the night. When the attack resumed the next morning, the Japanese were pushed to the cliff line where they hid below the cliff’s edge out of view. They were forced out of the caves and into the sea. It was at that time that the tanks were released to return to the 192nd and the 45th mopped up the Japanese.

The reality was that the same illnesses that were taking their toll on the Bataan defenders were also taking their toll on the Japanese. American newspapers wrote about the lull in the fighting and the building of defenses against the expected assault that most likely would take place. The soldiers on Bataan also knew that an assault was coming, they just didn’t know when it would take place. The newspapers in the U.S. wrote about the lull in Bataan and the preparations for the expected offensive.

Having brought in combat-harden troops from Singapore, the Japanese launched a major offensive on April 3rd supported by artillery and aircraft. The artillery barrage started at 10 AM and lasted until noon and each shell seemed to be followed by another that exploded on top of the previous shell. At the same time, wave after wave of Japanese bombers hit the same area dropping incendiary bombs that set the jungle on fire. The defenders had to choose between staying in their foxholes and being burned to death or seeking safety somewhere else. As the fire approached their foxholes those men who chose to attempt to flee were torn to pieces by shrapnel. It was said that arms, legs, and other body parts hung from tree branches. A large section of the defensive line at Mount Samat was wiped out. The next day a large force of Japanese troops came over Mt. Samat and descended the south face of the volcano. This attack wiped out two divisions of defenders and left a large area of the defensive line open to the Japanese.

A Co. was attached to the 194th Tank Battalion and was on beach duty with A Co., 194th. When the breakthrough came, the two tank companies were directly in the path of the advance. When the Japanese attempted to land troops, their smoke screen blew into their troops causing them to withdraw.

On April 7th, the 57th Infantry, Philippine Scouts, supported by tanks, attempted to restore the line, but Japanese infiltrators prevented this from happening. During this action, one tank was knocked out but the remaining tanks successfully withdrew. C Company, 194th, which was attached to the 192nd, had only seven tanks left. The Japanese attacked the line held by American troops on April 8th. It was said that the Japanese made what the Americans called “A Bridge of Death” where the Japanese threw themselves on the barbed wire until there were enough bodies on it so the following troops could walk over it. The defenders were not only defending against a frontal attack, but they also were defending against attacks on their flanks and rear.

It was the evening of April 8th that Gen. King decided that further resistance was futile, since approximately 25% of his men were healthy enough to fight, and he estimated they would last one more day. In addition, he had over 6,000 troops who were sick or wounded and 40,000 civilians who he feared would be massacred. His troops were on one-quarter rations, and even at that ration, he had two days of food left. He also believed his troops could fight for one more day. Companies B and D, 192nd, and A Company, 194th, were preparing for a suicide attack on the Japanese in an attempt to stop the advance. At 6:00 P.M. tank battalion commanders received this order: “You will make plans, to be communicated to company commanders only, and be prepared to destroy within one hour after receipt by radio, or other means, of the word ‘CRASH’, all tanks and combat vehicles, arms, ammunition, gas, and radios: reserving sufficient trucks to close to rear echelons as soon as accomplished.”

It was at 10:00 P.M. that the decision was made to send a jeep – under a white flag – behind enemy lines to negotiate terms of surrender. The problem soon became that no white cloth could be found. Phil Parish, a truck driver for A Company, realized that he had white bedding buried in the back of his truck and searched for it. The bedding became the “white flags” that were flown on the jeeps. At 11:40 P.M., the ammunition dumps were destroyed. At midnight Companies B and D, and A Company, 194th, received an order from Gen. Weaver to stand down. At 2:oo A.M. on April 9th, Gen. King sent a jeep under a white flag carrying Colonel Everett C. Williams, Col. James V. Collier, and Major Marshall Hurt to meet with the Japanese commander about terms of surrender. (The driver was from the tank group.) Shortly after daylight Collier and Hunt returned with word of the appointment. It was at about 6:45 A.M. that tank battalion commanders received the order “crash.”

That night as they attempted to sleep, the ground began to shake. They were experiencing an earthquake. They also heard the sound of explosions to the south of their bivouac. The rumor quickly spread that the Japanese had landed behind their position. In reality, they were hearing the ammunition dumps being blown up.

Shortly after daylight Collier and Hunt returned with word of the appointment. It was at about 6:45 A.M. that tank battalion commanders received the order “crash.” As Gen. King left to negotiate the surrender, he went through the area held by B Company and the 17th Ordnance Company and spoke to the men. He said to them, “Boys. I’m going to get us the best deal I can. When you get home, don’t ever let anyone say to you; you surrendered. I was the one who surrendered.” Gen. King with his two aides, Maj. Wade R. Cothran and Captain Achille C. Tisdelle Jr. got into a jeep carrying a large white flag. Another jeep followed them – also flying another large white flag – with Col. Collier and Maj. Hurt in it. As the jeeps made their way north, they were strafed and small bombs were dropped by a Japanese plane. The drivers of both jeeps managed to avoid the bullets. The strafing ended when a Japanese reconnaissance plane ordered the fighter pilot to stop strafing.

At about 10:00 A.M. the jeeps reached Lamao where they were received by a Japanese Major General who informed Gen. King that he reported his coming to negotiate a surrender and that an officer from the Japanese command would arrive to do the negotiations. The Japanese officer also told him that his troops would not attack for thirty minutes while King decided what he would do. No Japanese officer had arrived from their headquarters and the Japanese attack had resumed.

King sent Col. Collier and Maj. Hunt back to his command with instructions that any unit in the line of the Japanese advance should fly white flags. After this was done a Japanese colonel and interpreter arrived and King was told the officer was Homma’s Chief of Staff who had come to discuss King’s surrender. King attempted to get assurances from the Japanese that his men would be treated as prisoners of war, but the Japanese officer – through his interpreter – accused him of declining to surrender unconditionally. At one point King stated he had enough trucks and gasoline to carry his troops out of Bataan. He was told that the Japanese would handle the movement of the prisoners. The two men talked back and forth until the colonel said through the interpreter, “The Imperial Japanese Army are not barbarians.” King found no choice but to accept him at his word.

Unknown to Gen. King, an order attributed to Gen. Masaharu Homma – but in all likelihood from one of his subordinates – had been given. It stated, “Every troop which fought against our army on Bataan should be wiped out thoroughly, whether he surrendered or not, and any American captive who is unable to continue marching all the way to the concentration camp should be put to death in the area of 200 meters off the road.”

The medical detachment was bivouacked in an area next to HQ Company, 192nd, on the west side of the Bataan Peninsula. Around 3:00 A.M. on April 9, 1942, the rest of the medical detachment was informed of the surrender. A rumor soon spread that they were going to be put on barges and taken to Australia. Instead, they were sent to C Company’s bivouac. They stayed in its bivouac for two days before the Japanese made contact with them. It wasn’t until 5:00 P.M., on the 11th that they were ordered to Mariveles. The members of the medical detachment boarded their trucks and began to drive to Mariveles. On their way to Mariveles, the trucks were stopped by Japanese soldiers who took their watches. The men continued to Mariveles and ran into two Japanese soldiers who did not know what to do with them, so one went to get their commanding officer. While they waited, the remaining Japanese soldiers began bragging about how Japan had conquered the Philippines and would conquer Australia and the west coast of the United States.

Later in the day, the men were ordered to move. They had no idea that they had started what they simply called, “the march.” Most of the men had dysentery, some malaria, and others were simply weak from hunger. The first five miles were uphill which was hard on the sick men. It was made harder by the Japanese guards who were assigned a certain distance to march and made the POWs move at a faster pace so that they could complete their distance as fast as possible. Those who could not keep up and fell were bayoneted. At one point they ran past Japanese artillery that was firing at Corregidor with Corregidor returning fire. Shells began landing among the POWs who had no place to hide and some of the POWs were killed by incoming shells. Corregidor did destroy three of the four guns.

The Americans were marched in groups of 100 with guns on them at all times. Each group was assigned six Japanese guards who would be changed at regular intervals. Since the guards had a certain distance to cover, they wanted to do it as fast as possible and made the POWs move as fast as possible. Men who fell were shot or bayoneted because the guards did not want to stop for them. When the guards were replaced, the POWs again found themselves moving at a fast pace because they also wanted to complete their assigned portion of the march as fast as possible.

The heat on the march was intolerable, and those who begged for water were beaten by the guards with their rifle butts because they had asked. Those who were exhausted or suffering from dysentery and dropped to the side of the road were shot or clubbed to death. Food on the march was minimal when it was given to the prisoners, each would receive a pint of boiled rice. The Filipino people seeing the condition of the prisoners attempted to aid them by passing food to the Americans. If the Filipinos were caught doing this, they were beheaded. The further north they marched the more bloated dead bodies they saw. The ditches along the road were filled with water, but many also had dead bodies in them. The POWs’ thirst got so bad they drank the water. Many men would later die from dysentery.

What he said about the march was, “The Japs didn’t feed us much and there was no excuse for it, as there was plenty of food on the islands. A person could live off the land if free, as there was plenty of fruit and other foods available.”

As a medic, Marvin attempted to help the sick and weak as they struggled. However, the attitude of the Japanese guards made this extremely difficult. He watched as those who fell out were shot or bayoneted because they had malaria. In his opinion, many who fell out mentally found it too hard to go on.

During the 70-mile march, the Americans were seldom allowed to stop and were not fed until the fifth day. Those who stopped or dropped out were bayoneted. For the men, hearing other men who had fallen to the ground begging for help and not being able to stop to help them was one of the hardest things they experienced on the march. The POWs who continued to march and those who had fallen both knew that to do so meant death for both men.

The lack of water and food was extremely hard on the POWs. The POWs who ran to the water spigots of the artesian wells to fill their canteens with water were shot by the Japanese. The further north they marched the more bloated dead bodies they saw. The POWs were amazed by the courage of the Filipino people who openly defied the Japanese by giving food and water to the POWs. It was said that every 200 or 300 yards were artesian wells, but the POWs were not allowed to drink from them. As men became more desperate, they would run to the wells only to find that the Japanese had sent advance teams ahead who shot or bayoneted those attempting to get water from them. The ditches along the road were filled with water, but many also had dead bodies in them. The POWs’ thirst got so bad some chose to drink the water, and many of these men later died from dysentery. The column of POWs was often stopped and pushed off the road and made to sit in the sun for hours. While they sat there, the guards would shake them down and take any possession they had that the guards liked. When they were ordered to move again, it was not unusual for the Japanese to ride past them in trucks and entertain themselves by swinging at the POWs with their guns or with bamboo poles.

When they were north of Hermosa, the POWs reached pavement which made the march easier. They received an hour break, but any POW who attempted to lay down was jabbed with a bayonet. After the break, they marched through Layac and LubAt this time, that a heavy shower took place and many of the men opened their mouths to get water. The guards allowed the POWs to lie on the road. The rain revived many of the POWs and gave them the strength to complete the march. Jim recalled that it felt like his skin was actually absorbing the rain.

The men were marched until they reached San Fernando. Once there, they were herded into a bullpen, surrounded by barbed wire, and put into groups of 200 men. One POW from each group went to the cooking area which was next to the latrine and got food for the group. Each man received a ball of rice and four or five dried onions. Water was given out with each group receiving a pottery jar of water to share.

At some point, the POWs were ordered to form 100 men detachments and march to the train station in San Fernando. There, they were put into small wooden train cars known as “Forty or Eights” because each car could hold forty men or eight horses. Since each detachment had 100 men in it, the Japanese packed 100 men into each boxcar. Then they closed the doors. The heat was suffocating and those men who died could not fall to the floors since there was no room for them to fall. When the living left the boxcars at Capas, the dead fell to the floors. As the POWs left the cars, the Filipinos threw food to the POWs. The guards did not stop the Filipinos.

Marvin attempted to give first aid to those men who were sick or dying. In particular, he worked with those men suffering from malaria. This job was impossible because the doctors and medics had no medicine to treat the sick. Sixty men died a day because of the lack of medicines to treat them.

The Japanese finally acknowledged that they needed to do something to lower the death rate among the POWs so they opened a new camp at Cabanatuan. Only the POWs who were considered too ill to be moved remained behind at Camp O’Donnell. Records show that most of those POWs died. Although he was a medic, it is not known Marvin moved to Cabanatuan at this time.

Sometime during May, his family received this message from the War Department.

Dear Mr. F. Jaeger:

According to War Department records, you have been designated as the emergency addressee of Private Marvin W. Jaeger, 36,206,306, who, according to the latest information available, was serving in the Philippine Islands at the time of the final surrender.

I deeply regret that it is impossible for me to give you more information than is contained in this letter. In the last days before the surrender of Bataan, there were casualties which were not reported to the War Department. Conceivably the same is true of the surrender of Corregidor and possibly other islands of the Philippines. The Japanese Government has indicated its intention of conforming to the terms of the Geneva Convention with respect to the interchange of information regarding prisoners of war. At some future date, this Government will receive through Geneva a list of persons who have been taken prisoners of war. Until that time the War Department cannot give you positive information.

The War Department will consider the persons serving in the Philippine Islands as “missing in action” from the date of surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received. It is to be hoped that the Japanese Government will communicate a list of prisoners of war at an early date. At that time you will be notified by this office in the event that his name is contained in the list of prisoners of war. In the case of persons known to have been present in the Philippines and who are not reported to be prisoners of war by the Japanese Government, the War Department will continue to carry them as “missing in action” in the absence of information to the contrary, until twelve months have expired. At the expiration of twelve months and in the absence of other information the War Department is authorized to make a final determination.

Recent legislation makes provision to continue the pay and allowances of persons carried in a “missing” status for a period not to exceed twelve months; to continue, for the duration of the war, the pay and allowances of persons known to have been captured by the enemy; to continue allotments made by missing personnel for a period of twelve months and allotments or increase allotments made by persons by the enemy during the time they are so held; to make new allotments or increase allotments to certain dependents defined in Public Law 490, 77th Congress. The latter dependents generally include the legal wife, dependent children under twenty-one years of age, and dependent mother, or such dependents as having been designated in official records. Eligible dependents who can establish a need for financial assistance and are eligible to receive this assistance the amount allotted will be deducted from pay which would otherwise accrue to the credit of the missing individual.

Very Truly yours

J. A. Ulio (signed)

Major General

The Adjutant General

Marvin recalled, “No one had a bath at Cabanatuan from the time we reached there early in June until we left November 23, 1944.” He also believed that the camp guards broke the POWs’ arms and legs, “just to show their authority.”

From September to December, the Japanese issued identification numbers. The first POWs to receive them sailed for Manchuria on the Tottori Maru on October 8th. Marvin was issued number 1-06929 which was his POW number no matter where he was sent in the Philippines.

The Japanese announced to the POWs in the camp that on October 14th the daily food ration for each POW would be 550 grams of rice, 100 grams of meat, 330 grams of vegetables, 20 grams of fat, 20 grams of sugar, 15 grams of salt, and 1 gram of tea. In reality, the POWs noted that the meals were wet rice and rice coffee for breakfast, Pechi green soup and rice for lunch, and Mongo bean soup, Carabao meat, and rice for dinner.

The day started an hour before dawn when the POWs were awakened. They then lined up and bongo (roll call) was taken. The POWs quickly learned to count off quickly in Japanese because the POWs who were slow to respond were hit with a heavy rod. A half-hour before dawn was breakfast, and at dawn, they went to work. Those working on details near the camp returned to the camp for lunch, a tin of rice, at 11:30 AM and then returned to work. The typical workday lasted 10 hours.

The POWs were sent out on work details near the camp to cut wood for the POW kitchens. Other POWs worked in rice paddies. When working in the rice paddies, the POWs not only planted rice but also massaged the rice. This meant that 50 POWs lined up at the end of a rice paddy in four to six inches of water. Then arm to arm about a foot apart they stoop over and go to the other side. The purpose of this was to work the mud around the plants. The Japanese always stopped the POWs before they got to the other side. The POWs found out there were poisonous water snakes that were black that moved ahead of them as they did this. The guards stopped the POWs so they could kill the snakes and prevent them from being bitten.

Returning from a detail the POWs bought or were given, medicine, food, and tobacco, which they somehow managed to get into the camp even though they were searched when they returned. The worst detail the POWs worked on was the latrine detail where the POWs cleaned the Japanese latrines with their bare hands. The POWs removed the feces and put it in 55-gallon drums. It is not known what happened to the feces, but it is known it was often used as fertilizer by the Japanese. Returning from the work details in the evening, the POWs – even though they were searched – somehow managed to bring medicine, food, and tobacco into the camp. The POWs ate supper but after they finished there wasn’t much time for them to do anything since dusk was an hour after supper. Later, the POWs had books to read that were sent by the Red Cross.

The POWs were organized in groups on November 11th. Group I was made up of all the enlisted men who had been captured on Bataan. Group II was the POWs who had come from Camp 3, and Group III was composed of all Naval and Marine personnel from both Camps 1 and 3 and any civilians in the camp. It was also at this time that an attempt was made to stop the spread of disease. The POWs dug deep drainage ditches, and sump holes for only water, and the garbage began to be buried, and the grass in the camp was cut. 100 POWs worked on Sunday, November 15th digging latrines and sump holes. Since Sunday was a day off, Lt. Col. Curtis Beecher, U.S.M.C., made sure each man received 5 cigarettes. On November 16th, a Pvt. Peter Laniauskas was shot trying to escape. Two other POWs were tried by the Japanese for being involved in the escape attempt. One man received 20 days in solitary confinement and the other 30 days.

Fr. Antonio Bruddenbruck, a German Catholic priest, came to the camp – assisted by Mrs. Escoda – with packages from friends and relatives in Manila on November 12th. There was also medicine and books for the POWs. The POWs started a major clean-up of the camp on November 14th and deep latrines, sump holes for water only, and began to bury the camp’s garbage. Pvt. Peter Lankianuskas was shot while attempting to escape on November 16th. Two other POWs were put on trial by the Japanese for aiding him. One man received 20 days in solitary confinement while the other man received 30 days in solitary confinement. Pvt. Donald K. Russell, on November 20th, was caught trying to reenter the camp at 12:30 A.M. He had left the camp at 8:30 P.M. and secured a bag of canned food by claiming he was a guerrilla. He was executed in the camp cemetery at 12;30 P.M. on November 21st. The Japanese gave out a large amount of old clothing – that came from Manila – to the POWs on November 22nd. On November 23rd, a detachment of POWs left the camp for Ft, McKinley. Marvin was one of the POWs in the detachment.

It appears that he was selected for a work detail at this time. The date when the POWs arrived at Ft. McKinley varies from source to source. Some sources state they arrived on October 12th while other sources state that the first POW detachment sent to Ft. McKinley arrived on November 23rd. All sources agree that the POW detachment was made up of 270 men. There, the POWs did cleanup work clearing the grounds of junk from the battle. The POWs lived in the two-story barracks of the 45th Infantry Division, Philippine Scouts. The entire POW compound covered an area of 300 feet by 150 feet that the POWs were allowed to walk around. The POWs lived in the upper and lower squad rooms and the rest spread throughout the rest of the building. Since there was limited room, the men slept shoulder to shoulder on sawale floor mats and in ten men mosquito nets issued by the Japanese. Blankets were also issued, but there were several POWs without them. No furniture was provided, but they were able to get chairs and tables from nearby buildings. The POWs washed their clothes in buckets that they found or made. When the detail started, the POWs were issued coconut fiber hats and shoes. Both these items did not last long on the detail.

The latrines in the camp had three stalls, a four-foot urinal, a tray sink with five spigots, and a shower room with four showerheads. Because of the demand on the facilities in the morning and evening about one-fourth of these were out of service at any time. Because of the lack of proper materials, the POWs were unable to keep all the showers functioning despite their best efforts.

The POW kitchen was in a stone building that was fifty feet from the POW barracks. Meals for the men were prepared in four halved oil drums that served as stoves that had no grates or chimneys to vent smoke. Cooking utensils consisted of four rice pots, two knives, an icebox, and an old well perforated Army-issued stove. The POWs also managed to get a meat grinder, several more knives, and a wooden chopping block. A pool table became the main food preparation table in the kitchen. Water spigots were added and the water drained into the floor and out of the building through holes the POWs chiseled through the wood. Waste from the kitchen was hauled away by Filipinos and burnt.

The POWs ate their meals on the second floor of a barracks that served as a mess hall with the Japanese quarters on the first floor. There were enough tables and benches for every POW, and the meals were carried to them in five-gallon drums. About 80% of the POWs had mess kits with the other 20% using pottery plates, tin pans, and tin cans. They were able also to clean their mess gear.

The camp medical facilities were two small rooms served as a hospital but there was no medical equipment or supplies until December 1942. A table that was found in a nearby building was used for examinations under a 40-watt light bulb. Water – when needed – came from a latrine twenty feet away from the infirmary. POWs who were ill were not required to work. Requests for medical supplies to the Japanese commanding officer were ignored. Most of the POWs treated at the hospital had foot or leg injuries since they worked without shoes.

The POWs were moved to Nielson Field. Some sources state the move took place on January 20, 1943, while others state it happened on January 29, 1943. For the first six weeks, the POWs marched 8 kilometers to the airfield each morning and marched 8 kilometers back to their barracks in the evening. Later, they rode trucks to the airfield. Some sources also state the compound was 500 feet by 200 feet and surrounded by barbed wire while others state it was approximately 300 feet by 200 feet. These may simply be the dimensions for each of the POW compounds.

The POWs were soon moved to Camp Nielsen where they lived in four Nipa barracks that were 150 feet long by 20 feet wide which had been built for them. Each barrack had a six-foot-wide aisle down the center with sleeping platforms along the walls. One-quarter of the space was used for sleeping quarters for the officers which meant the enlisted POWs slept shoulder to shoulder again. The center aisle was lit by a 40-watt light bulb located above the center aisle. One barracks contained the camp’s medical facility which occupied a quarter of the building. There were two 7-foot-long shelves on each wall that served as beds for the sick. There were no medical supplies or equipment. The area was lit by the one 40-watt bulb in the barrack and even though the POW doctor requested more lighting be provided, and was assured it would be dealt with, nothing was ever done. Again, most of the POWs suffered leg or foot injuries.