2nd Lt. William Woodgate Read was the son of Arthur D. Read and Ethel F. Woodgate-Read of West Monroe, Louisiana. He was born on February 8, 1920, in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and had two sisters and two brothers. He was known as “Bill” to his family and friends. When he was a child, Bill’s family moved to Louisiana. There, he graduated, with honors, from Bolton High School in Alexandria, Louisiana, in 1936. While in high school, he participated in debate, tennis, and the National Honor Society. It also appears that he joined the Louisiana National Guard around this time.

After high school, he attended the University of Idaho where he chose to major in forestry which was the area his father worked in professionally. While in college, Bill, was a member of Phi Eta Sigma an honorary fraternity. He received this honor for achieving a grade point average of 5.5 or higher. He was also a member of Xi Sigma Pi an honorary forestry fraternity, the Associated Foresters, a member of the staff of the Idaho Forester, the Delta Tau Delta Fraternity, and the ROTC program at the university. He graduated from college, with honors, in June 1941. After graduation, he attended the Louisiana National Guard’s Officers Candidates School in the summer of 1941 and was commissioned a second lieutenant on July 18, 1941. The 753rd Tank Battalion was activated on June 1, 1941, at Camp Polk, Louisiana. Upon completion of the OCS on Sept. 1, 1941, he was sent to Camp Polk, Louisiana, and assigned as a tank platoon commander in A Company, 753rd Tank Battalion.

The Louisiana maneuvers started in September 1941 but the 753rd did not take part in them. Most likely because the battalion was still training. After the maneuvers, the 192nd Tank Battalion – which did participate in the maneuvers – was ordered to Camp Polk. It was on the side of a hill that the battalion was informed it was going overseas. The members of the 192nd who were married with dependents, with other dependents, 29 years old or older, or whose National Guard enlistments would end while the battalion was overseas, were allowed to resign from federal service. The battalion’s commander, because of his age, was replaced by Major. Theodore Wickord his executive officer. Replacements for the men came from the 753rd Tank Battalion. One of those replacements was William. It is not known if he volunteered to join the battalion or if he became a member of the battalion after his name was drawn from a hat. After joining the battalion, he was assigned to A Company and became a tank platoon commander. He also went from living in a barrack to living in a tent with other officers of the company which was made worse since it seemed to rain every day while they were at Camp Polk.

The 192nd boarded the USAT Gen. Hugh L. Scott and sailed on Monday, October 27th. The sea was rough during this part of the trip, so many tankers had seasickness and also had a hard time walking on deck until they got their “sea legs.” It was stated that about one-tenth of the battalion showed up for inspection the first morning on the ship. Once they recovered they spent much of the time training in breaking down machine guns, cleaning weapons, and doing KP.

During this part of the trip, one of the soldiers had an appendectomy. A day or two before the ships arrived in Hawaii, the ships ran into a school of flying fish. Since the sea was calm, that night they noticed the water was a phosphorous green. The sailors told them that it was St. Elmo's Fire. The ship arrived at Honolulu, Hawaii, on Sunday, November 2nd, and had a four-day layover. As the ship docked, men threw coins in the water and watched native boys dive into the water after them. They saw two Japanese tankers anchored in the harbor that arrived to pick up oil but had been denied permission to dock.

The morning they arrived in Hawaii was said to be a beautiful sunny day. Most of the soldiers were given shore leave so they could see the island. During this time they visited pineapple ranches, coconut groves, and Waikiki Beach which some said was nothing but stones since it was man-made. They also noticed that the island residents were more aware of the impending war with Japan. Posters were posted everywhere. Most warned sailors to watch what they said because their spies and saboteurs on the island. Other posters in store windows sought volunteers for fire-fighting brigades. Before they left Hawaii, an attempt was made to secure two 37-millimeter guns and ammunition so that the guns could be set up on the ship’s deck and the tank crews could learn how to load them and fire them, but they were unable to acquire the guns.

Bill attempted to raise the morale of the soldiers by providing them with information on the Philippines. He had taken the time to learn as much as he could about the islands and their people and would hold his information lectures on deck. For many of the soldiers, these sessions were appreciated since they were often seasick and the sessions relieved their boredom.

Before the ship sailed, an attempt was made to secure two 37-millimeter guns and ammunition so that the guns could be set up on the ship’s deck and the tank crews could learn how to load them and fire them, but they were unable to acquire the guns. On Thursday, November 6th, the ship sailed for Guam but took a southerly route away from the main shipping lanes. It was at this time it was joined by, the heavy cruiser, the USS. Louisville, and, another transport, the USAT President Calvin Coolidge. The ships headed west in a zig-zag pattern. Since the Scott had been a passenger ship, they ate in large dining rooms, and it was stated the food was better than average Army food. As the ships got closer to the equator the hold they slept in got hotter and hotter, so many of the men began sleeping on the ship's deck. They learned quickly to get up each morning or get soaked by the ship's crew cleaning the decks. Sunday night, November 9th, the soldiers went to bed and when they awoke the next morning, it was Tuesday, November 11th. During the night, while they slept, the ships crossed the International Dateline. Two members of the battalion stated the ship made a quick stop at Wake Island to drop off a radar crew and equipment.

During this part of the voyage that lasted 16 days, fire drills were held every two days, the soldiers spent their time attending lectures, playing craps and cards, reading, writing letters, and sunning themselves on deck. Other men did the required work like turning over the tanks’ engines by hand and the clerks caught up on their paperwork. The soldiers were also given other jobs to do, such as painting the ship. Each day 500 men reported to the officers and needle-chipped paint off the lifeboats and then painted the boats. By the time they arrived in Manila, every boat had been painted. Other men not assigned to the paint detail for that day attended classes. In addition, there was always KP.

Two men stated that the ship made a stop at Wake Island, but this has not been verified. It is known that around this time, radar equipment and its operators arrived on the island. On Saturday, November 15th, smoke from an unknown ship was seen on the horizon. The Louisville revved up its engines, its bow came out of the water, and it took off in the direction of the smoke. It turned out that the unknown ship was from a friendly country. Two other intercepted ships were Japanese freighters hauling scrap metal to Japan.

Albert Dubois, A Co., stated that they were in a room on the ship and listening to the radio. Recalling the event, he said, "We were playing cards one day at sea. President Roosevelt's speech to America was being piped into the room we were in. I still hear his voice that evening in November 1941. 'I hate war, Eleanor hates war. We all hate war. Your sons will not and shall not go overseas!' We were already halfway to the Philippines."

After sailing, the ship took the southern route away from the main shipping lanes. While at sea, it was joined by the SS President Calvin Coolidge and heavy cruiser the USS Louisville which was the two ships military escort. At one point, smoke from an unknown ship was seen on the horizon, the Louisville's revved its engines, its bow came out of the water, and the ship shot off in the direction of the smoke. As it turned out the unknown ship was from a neutral country. When they arrived at Guam on Sunday, November 16th, the ships took on water, bananas, coconuts, and vegetables. Although they were not allowed off the ship, the soldiers were able to mail letters home before sailing for Manila the next day. At one point, the ships passed an island at night and did so in total blackout. This for many of the soldiers was a sign that they were being sent into harm’s way. The blackout was strictly enforced and men caught smoking on deck after dark spent time in the ship’s brig. Three days after leaving Guam the men spotted the first islands of the Philippines. The ships sailed around the south end of Luzon and then north up the west coast of Luzon toward Manila Bay.

The ships entered Manila Bay, at 8:00 A.M., on Thursday, November 20th, and docked at Pier 7 later that morning. One thing that was different about their arrival was that instead of a band and a welcoming committee waiting at the pier to tell them to enjoy their stay in the Philippines and see as much of the island as they could, a party came aboard the ship – carrying guns – and told the soldiers, “Draw your firearms immediately; we’re under alert. We expect a war with Japan at any moment. Your destination is Fort Stotsenburg, Clark Field.” At 3:00 P.M., as the enlisted men left the ship, a Marine was checking off their names. When an enlisted man said his name, the Marine responded with, “Hello sucker.” Those who drove trucks drove them to the fort, while the maintenance section remained behind at the pier to unload the tanks. Some men stated they rode a train to Ft. Stotsenburg while other men stated they rode busses to the base.

During the trip to the Philippines, Capt. Nelson left HQ Company and became the battalion's executive officer for a short time. He was promoted to major, on November 1, 1941. Capt. Fred Bruni became HQ Company's new commanding officer. The battalion boarded busses that took them to a train station, they then rode a train to the base. At the fort, the tankers were met by Gen. Edward P. King Jr. who welcomed them and made sure that they had what they needed. He also was apologetic that there were no barracks for the tankers and that they had to live in tents. The fact was he had not learned of their arrival until days before they arrived. He made sure that they had dinner – which was a stew thrown into their mess kits – before he left to have his own dinner. D Company was scheduled to be transferred to the 194th Tank Battalion so when they arrived at the fort, they most likely moved into their finished barracks instead of tents that the rest of the 192nd. The 194th had arrived in the Philippines in September and its barracks were finished about a week earlier. The company also received a new commanding officer, Capt. Jack Altman.

The other members of the 192nd pitched their tents in an open field halfway between the Clark Field Administration Building and Fort Stotsenburg. The tents from WW I and pretty ragged. They were set up in two rows and five men were assigned to each tent. There were two supply tents and meals were provided by food trucks stationed at the end of the rows of tents. Their tanks were in a field not far from the tanks. The worst part of being in the tents was that they were near the end of a runway. The B-17s when they took off flew right over the bivouac about 100 feet off the ground. At night, the men heard planes flying over the airfield. Many men believed they were Japanese, but it is known that American pilots flew night missions.

The 192nd arrived in the Philippines with a great deal of radio equipment to set up a radio school to train radiomen for the Philippine Army. The battalion also had many ham radio operators after arriving at Ft. Stotsenburg, the battalion set up a communications tent that was in contact with ham radio operators in the United States within hours. The communications monitoring station in Manila went crazy attempting to figure out where all these new radio messages were coming from. When they were informed it was the 192nd, they gave the 192nd frequencies to use. Men sent messages home to their families that they had arrived safely.

With the arrival of the 192nd, the Provisional Tank Group was activated on November 27th. Besides the 192nd, the tank group contained the 194th Tank Battalion with the 17th Ordnance Company joining the tank group on the 29th. Both units had arrived in the Philippines in September 1941. Military documents written after the war show the tank group was scheduled to be composed of three light tank battalions and two medium tank battalions. Col. Weaver left the 192nd, was appointed head of the tank group, and was promoted to brigadier general. Major Theodore Wickord permanently became the commanding officer of the 192nd.

The day started at 5:15 with reveille and anyone who washed near a faucet with running water was considered lucky. At 6:00 A.M. they ate breakfast followed by work – on their tanks and other equipment – from 7:00 A.M. to 11:30 A.M. Lunch was from 11:30 A.M. to 1:30 P.M. when the soldiers returned to work until 2:30 P.M. The shorter afternoon work period was based on the belief that it was too hot to work in the climate. The term “recreation in the motor pool,” meant they worked until 4:30 in the afternoon.

During this time, the battalion members spent much of their time getting the cosmoline out of the barrels of the tanks' guns. Since they only had one reamer to clean the tank barrels, many of the main guns were cleaned with a burlap rag attached to a pole and soaked in aviation fuel. It was stated that they probably only got one reamer because Army ordnance didn't believe they would ever use their main guns in combat. The tank crews never fired their tanks' main guns until after the war had started, and not one man knew how to adjust the sights on the tanks. The battalion also lost four of its peeps, later called jeeps, used for reconnaissance to the command of the United States Armed Forces Far East also known as USAFFE.

Before they went into the nearest barrio which was two or three miles away, all the newly arrived troops were assembled for a lecture by the post's senior chaplain. It was said that he put the fear of God and gonorrhea into them.

It is known that during this time the battalion went on at least two practice reconnaissance missions under the guidance of the 194th. It traveled to Baguio on one maneuver and to the Lingayen Gulf on the other maneuver. Gen. Weaver, the tank group commander, was able to get ammunition from the post’s ordnance department on the 30th, but the tank group could not get time at one of the firing ranges.

At Ft. Stotsenburg, the soldiers were expected to wear their dress uniforms. Since working on the tanks was a dirty job, the battalion members wore coveralls to work on the tanks. The 192nd followed the example of the 194th Tank Battalion and wore coveralls in their barracks area to do work on their tanks, but if the soldiers left the battalion’s area, they wore dress uniforms – which were a heavy material and uncomfortable to wear in the heat – everywhere; including going to the PX.

For recreation, the soldiers spent their free time bowling or going to the movies on the base. They also played horseshoes, softball, and badminton, or threw footballs around during their free time. On Wednesday afternoons, they went swimming. Passes were given out and men were allowed to go to Manila in small groups.

When the general warning of a possible Japanese attack was sent to overseas commands on November 27th, the Philippine command did not receive it. The reason why this happened is not known and several reasons for this can be given. It is known that the tanks took part in an alert that was scheduled for November 30th. What was learned during this alert was that moving the tanks to their assigned positions at night would be a disaster. In particular, the 194th’s position was among drums of 100-octane gas, and the entire bomb reserve for the airfield and the bombs were haphazardly placed. On December 1st, the tankers were ordered to the perimeter of Clark Field to guard against Japanese paratroopers. From this time on, two tank crew members remained with each tank at all times and were fed from food trucks.

On Monday, December 1st, the tanks were ordered to the perimeter of Clark Field to guard against paratroopers. The 194th guarded the northern end of the airfield, while the 192nd guarded the southern end where the two runways came together and formed a V. Two members of every tank crew remained with their tanks at all times, and meals were brought to them by food trucks. On Sunday, December 7th, the tankers spent a great deal of the day loading bullets into machine gun belts and putting live shells for the tanks’ main guns into the tanks.

Gen. Weaver on December 2nd ordered the tank group to full alert. Weaver appeared to be the only officer on the base interested in protecting his unit. When Poweleit suggested they dig air raid shelters - since their bivouac was so near the airfield - the other officers laughed. He ordered his medics to dig shelters near the tents of the companies they were with and at the medical detachment's headquarters. On December 3rd the tank group officers had a meeting with Gen Weaver on German tank tactics. Many believed that they should be learning how the Japanese used tanks. That evening when they met with Gen. Jonathan Wainwright, they concluded that he had no idea how to use tanks. It was said they were glad Weaver was their commanding officer. That night the airfield was in complete black-out and searchlights scanned the sky for enemy planes. All leaves were canceled on December 6th.

It was the men manning the radios in the 192nd communications tent who were the first to learn - at 2 a.m. - of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 8th. Major Ted Wickord, Gen. James Weaver, and Major Ernest Miller, 194th, and Capt. Richard Kadel, 17th Ordnance read the messages of the attack. At one point, even Gen. King came to the tent to read the messages. The officers of the 192nd were called to the tent and informed of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The 192nd's company commanders were called to the tent and told of the Japanese attack.

Most of the tankers heard about the attack on Pearl Harbor at roll call that morning. Some men believed that it was the start of the maneuvers they were expecting to take part in. They were also informed that their barracks were almost ready and that they would be moving into them shortly. News reached the tankers that Camp John Hay had been bombed at 9:00 a.m.

After hearing the news, Capt. Write went to his company and informed his men that Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor. To an extent, the news of the war was no surprise to the men, and many had come to the conclusion it was inevitable. The remaining members of the tank crews, not with their tanks, went to their tanks at the southern end of the Clark Field. The battalion’s half-tracks joined the tanks and took up positions next to them.

When the Japanese were finished, there was not much left of the airfield. The soldiers watched as the dead, dying, and wounded were hauled to the hospital on bomb racks, and trucks, and anything else that could carry the wounded was in use. Within an hour the hospital had reached its capacity. As the tankers watched the medics placed the wounded under the building. Many of these men had their arms and legs missing. When the hospital ran out of room, the battalion members set up cots under mango trees for the wounded and even the dentist gave medical aid to the wounded.

Sgt. Robert Bronge, B Co., had his crew take their half-track to the non-com club. During the 17 days that the 192nd had been in the Philippines, Bronge had spent three months of pay, on credit, at the non-com club. When they got to the club they found one side was collapsed from an explosion of a bomb nearby. Bronge entered the club and found the Aircorpsmen - assigned to the club - were putting out fires or trying to get the few planes that were left into the air. He found the book with the names of those who owed the club money and destroyed it. His crew loaded the half-track with cases of beer and hard liquor. When they returned to their assigned area at the airfield, they radioed the tanks they had salvaged needed supplies from the club.

The tank crews spent much of the time loading bullets by hand from rifle cartridges into machine gun belts since they had gone through most of their ordnance during the attack. That night, since they did not have any foxholes, the men used an old latrine pit for cover since it was safer in the pit than in their tents. The entire night they were bitten by mosquitoes. Without knowing it, they had slept their last night on a cot or bed, and from this point on, the men slept in blankets on the ground. One result of the attack was that D Company was never transferred to the 194th.

The tankers recovered the 50 caliber machine guns from the planes that had been destroyed on the ground and got most of them to work. They propped up the wings of the damaged planes so they looked like the planes were operational hoping this would fool the Japanese to come over to destroy them. The next day when the Japanese fighters returned, the tankers shot two planes down. After this, the planes never returned. It was at this time every man was issued Springfield and Infield rifles. Some worked some didn't so they cannibalized the rifles to get one good rifle from two bad ones.

The next morning the decision was made to move the battalion into a tree-covered area. Those men not assigned to a tank or half-track walked around Clark Field to view the damage. As they walked, they saw there were hundreds of dead. Some of the dead were pilots who had been caught asleep, because they had flown night missions, in their tents during the first attack. Others were pilots who had been killed attempting to get to their planes. The tanks were still at the southern end of the airfield when a second air raid took place on the 10th. This time the bombs fell among the tanks of the battalion at the southern end of the airfield wounding some men.

The tankers worked building makeshift runways away from Clark Field and digging a pit to put radio equipment for the airfield underground. While digging the pit, men stated they would never work in the pit. Seven or ten P-40s flew to the airfield and landed. All but one were later destroyed on the ground. The one plane that did get airborne was never seen again. When the airfield was attacked, all the men working in the radio pit were buried alive.

C Company was ordered to the area of Mount Arayat on December 9th. Reports had been received that the Japanese had landed paratroopers in the area. No paratroopers were found, but it was possible that the pilots of damaged Japanese planes may have jumped from them. That night, they heard bombers fly at 3:00 a.m. on their way to bomb Nichols Field. The battalion's tanks were still bivouacked among the trees when a second air raid took place on the 10th. This time the bombs fell among the tanks of the battalion at the southern end of the airfield wounding some men.

On the 10th, the half-tracks were in the battalion's area watching the airfield. A formation of Japanese bombers bombed the area. As the crews sat in the half-tracks a 500 bomb exploded about 500 feet from them. The bombs fell in a straight line toward the half-tracks. One bomb fell 25 feet from the half-tracks and then eighteen feet in front of the half-tracks. The final bomb fell about 250 feet behind the half-tracks. The shriek of the bombs falling scared the hell out of the men. T/4 Frank Goldstein radioed HQ and told them about the unexploded bombs. A bomb disposal squad was sent to the area. Later, a jeep pulled up and an officer and enlisted man marked where the sixteen unexploded bombs were located. The crew could see the smoke rising from the fuses of the unexploded bombs. Another jeep and a bulldozer arrived and dirt was pushed over the bombs. The half-track's crew radioed HQ and told them they were moving to the old tank park away from the bombs.

On December 12th, B Company was sent to the Barrio of Dau to guard a highway and railroad against sabotage. The other companies of the 192nd remained at Clark Field until December 14th, when they moved to a dry stream bed. Around December 15th, after the Provisional Tank Group Headquarters was moved to Manila, Major Maynard Snell, a 192nd staff officer, stopped at Ft. Stotsenburg where anything that could be used by the Japanese was being destroyed. He stopped the destruction long enough to get five-gallon cans loaded with high-octane gasoline and small arms ammunition put onto trucks to be used by the tanks and infantry

The tank battalion received orders on December 21st to proceed north to Lingayen Gulf to relieve the 26th Cavalry, Philippine Scouts. During this move, B Company rejoined the battalion. B and C Companies were sent north but because of logistics problems, they soon ran low on fuel. When they reached Rosario on the 22nd, there was only enough gas for one tank platoon, from B Company, to proceed north to support the 26th Cavalry. Lt. Ben Morin’s platoon approached Agoo when it ran head-on into a Japanese motorized unit. The Japanese light tanks had no turrets and sloped armor. The shells of the Americans glanced off the tanks. Morin’s tank was knocked out and his crew was captured. During this engagement, a member of a tank crew, Pvt. Henry J. Deckert, was killed by enemy fire and was later buried in a churchyard. This was the first tank action in World War II involving American tanks. The rest of the tanks never reached the landing area because they were ordered from the area because of the lack of fuel for them. The tanks served as a rear guard, from this time on, holding roads open until all the other troops withdrew before falling back to another predetermined position to repeat the action. The Provisional Tank Group Headquarters remained in Manila until December 23rd when it moved with the 194th north out of Manila.

The 192nd and part of the 194th fell back to a line from on the night of December 27th and 28th. From there they fell back to the south bank of the BamBan River which they were supposed to hold for as long as possible. Bill’s tank platoon served as the rear guard and knocked out Japanese tanks that were following them. A few days later on December 29th, east of Concepcion, A Company had bivouacked along both sides of a road and posted sentries. Night had fallen when the sentries heard a commotion from down the road and alerted the tankers. They grabbed their Tommy guns and waited in silence. As they watched a Japanese bicycle battalion rode into their bivouac. They held their fire until the last bicycle had passed when they opened fire. Screams and flashes of light as they fired were all that was heard and seen. When they ceased fire, they had completely wiped out the bicycle battalion.

The next morning, December 30th, Bill’s tank platoon was again serving as a rearguard near the Barrio of Zaragosa, His tank was in a dry rice paddy when it came under enemy fire by Japanese mortars. Bill was riding in a tank when one of the enemy rounds hit one of its tracks knocking it out. After escaping the tank, Bill stood in front of it and attempted to free the crew. A second round hit the tank, directly below where he was standing severely wounding his legs below the knees and leaving him mortally wounded. The other members of his crew carried Bill from the tank and laid him under in a culvert. Bill would not allow himself to be evacuated since there were other wounded soldiers. He insisted that these men be taken first.

Pvt. Jack Bruce went for help, but when he did not return quickly, Pvt. Eugene Greenfield went to find help in an attempt to save Bill’s life. Staying with Bill was Pvt. Ray Underwood. As Bill lay dying, Underwood cradled him in his arms. While Underwood sat with Bill, the Japanese overran the area. When Underwood was captured, he was sitting on the ground holding Bill in his arms as he died. Another version of the story states that after he and Underwood were captured, a Japanese officer killed Bill with his sword. Underwood would later receive a commendation for his actions while he was a Prisoner of War.

On Tuesday, December 30, 1941, 2nd Lt. William A. Read died of his wounds, in a culvert, during the Battle of the Luzon. His body was left along the side of the road. In April 1942, he was awarded the Purple Heart. When Bataan surrendered to the Japanese on April 9, 1942, Bill was considered a POW. A letter was sent to his family.

Dear Mrs. E. Read:

According to War Department records, you have been designated as the emergency addressee of Second Lieutenant William W. Read, O,423,832, who, according to the latest information available, was serving in the Philippine Islands at the time of the final surrender.

I deeply regret that it is impossible for me to give you more information than is contained in this letter. In the last days before the surrender of Bataan, there were casualties which were not reported to the War Department. Conceivably the same is true of the surrender of Corregidor and possibly other islands of the Philippines. The Japanese Government has indicated its intention of conforming to the terms of the Geneva Convention with respect to the interchange of information regarding prisoners of war. At some future date, this Government will receive through Geneva a list of persons who have been taken prisoners of war. Until that time the War Department cannot give you positive information.

The War Department will consider the persons serving in the Philippine Islands as “missing in action” from the date of surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received. It is to be hoped that the Japanese Government will communicate a list of prisoners of war at an early date. At that time you will be notified by this office in the event that his name is contained in the list of prisoners of war. In the case of persons known to have been present in the Philippines and who are not reported to be prisoners of war by the Japanese Government, the War Department will continue to carry them as “missing in action” in the absence of information to the contrary, until twelve months have expired. At the expiration of twelve months and in the absence of other information the War Department is authorized to make a final determination.

Recent legislation makes provision to continue the pay and allowances of persons carried in a “missing” status for a period not to exceed twelve months; to continue, for the duration of the war, the pay and allowances of persons known to have been captured by the enemy; to continue allotments made by missing personnel for a period of twelve months and allotments or increase allotments made by persons by the enemy during the time they are so held; to make new allotments or increase allotments to certain dependents defined in Public Law 490, 77th Congress. The latter dependents generally include the legal wife, dependent children under twenty-one years of age, and dependent mother, or such dependents as having been designated in official records. Eligible dependents who can establish a need for financial assistance and are eligible to receive this assistance the amount allotted will be deducted from pay which would otherwise accrue to the credit of the missing individual.

Very truly yours

J. A. Ulio (signed)

Major General

The Adjutant General

Although he was believed dead, since his death could not be confirmed he was considered Missing in Action. In May 1943, his family received a letter from the War Department that was part of a mass mailing sent to all families who had relatives on Bataan and Corregidor.

Dear Mrs. A Read:

According to War Department records, you have been designated as the emergency addressee if 1st Lt. William W. Read, O,423,832, who, according to the latest information available, was serving in the Philippine Islands at the time of the final surrender.

I deeply regret that it is impossible for me to give you more information than is contained in this letter. In the last days before the surrender of Bataan, there were casualties which were not reported to the War Department. Conceivably the same is true of the surrender of Corregidor and possibly other islands of the Philippines. The Japanese Government has indicated its intention of conforming to the terms of the Geneva Convention with respect to the interchange of information regarding prisoners of war. At some future date, this Government will receive through Geneva a list of persons who have been taken prisoners of war. Until that time the War Department cannot give you positive information.

The War Department will consider the persons serving in the Philippine Islands as “missing in action” from the date of surrender of Corregidor, May 7, 1942, until definite information to the contrary is received. It is to be hoped that the Japanese Government will communicate a list of prisoners of war at an early date. At that time you will be notified by this office in the event that his name is contained in the list of prisoners of war. In the case of persons known to have been present in the Philippines and who are not reported to be prisoners of war by the Japanese Government, the War Department will continue to carry them as “missing in action” in the absence of information to the contrary, until twelve months have expired. At the expiration of twelve months and in the absence of other information the War Department is authorized to make a final determination.

Recent legislation makes provision to continue the pay and allowances of persons carried in a “missing” status for a period not to exceed twelve months; to continue, for the duration of the war, the pay and allowances of persons known to have been captured by the enemy; to continue allotments made by missing personnel for a period of twelve months and allotments or increase allotments made by persons by the enemy during the time they are so held; to make new allotments or increase allotments to certain dependents defined in Public Law 490, 77th Congress. The latter dependents generally include the legal wife, dependent children under twenty-one years of age, and dependent mother, or such dependents as having been designated in official records. Eligible dependents who can establish a need for financial assistance and are eligible to receive this assistance the amount allotted will be deducted from pay which would otherwise accrue to the credit of the missing individual.

Very truly yours

(signed)

J. A. JULIO

Major General

The Adjutant General

His family received another letter in May 1944, that continued his status as Missing in Action throughout the war. On May 9, 1945, after the records kept by the POWs in Camp O’Donnell POW Camp, Cabanatuan POW Camp, and in Bilibid Prison were recovered in January and February 1945, was his date of death confirmed as Dec. 30, 1941, that his family received a letter from the War Department on, confirming his death.

When the POWs at Cabanatuan and Bilibid Prison were liberated in January and February 1945, respectively, the death records kept in Camp O’Donnell, Cabanatuan, Bilibid Prison, and from work details were recovered. It was from those records that the actual dates of death for men who had been declared dead were learned.

Bill’s family also learned the details of his death from and interview that 1st Sgt. Dale Lawton gave to the Janesville Gazette who had been liberated at Cabanatuan. Lawton – when he wrote a letter to them on May 3, 1945 – told them of the events leading to Bill’s death. Lawton had been told the details of Bill’s death by Pvt. Ray Underwood. He also wrote to Bill’s parents, “I don’t know why the lieutenant’s death was not reported to the government as it was reported over there to (battalion) headquarters. I don’t know what was done with the lieutenant’s body. This happened near Carmen. I gave the story last to the officers in Washington, D.C. when I was there last week.” On May 9, 1945, his family received a telegram from the War Department confirming his death. This was followed by letter. Bill was posthumously promoted to First Lieutenant on June 6, 1945, effective De. 29, 1941. In 1947, he was posthumously awarded the Silver Star for gallantry.

Sgt. Owen Sandmire, A Co. also wrote to Bill’s parents on Sept, 17, 1945, and told them that the action took place “on a lonely road into the woods and was buried in the woods near the road.” It was believed that Sandmire had talked with Underwood who provided the information to him.

When the American Graves Registration Service recovery team arrived in Zaragosa, Nueva Ecija, on Oct. 1, 1948, it was informed by the Chief of Police that a Lt. William W. Read was buried at a certain location. They went to location and found it flooded by a stream so the damned the stream. After two days of digging, they found nothing. During the second day, a man watching them work told them they were digging in the wrong place. He told them his son had buried the American and took the team to his home. The man’s son, Eusebio Mercado, took the team to a spot that was 20 feet from where they had been digging and pointed. He also drew a map and told the recovery team that he had buried an American tank officer on Dec. 31, 1941. He stated that he had buried a Lt. William W. Read along the side of the road in the Barrio of Santa Rosa, Nueva Ecija and taken his identification tags which he lost during the occupation. A recovery team went to the location and 20 minutes after they began digging they found Read’s remains. Read was identified because of Mercado knowing his identification number, and according to his Individual Deceased Personnel File, when the grave was exhumed they found GI shoes on his feet, tank goggles, a canteen cup, a coverall buckle. Mercado also knew Read’s service number.

The Quartermaster Corps sent a letter to his father, Arthur, on Jan. 29, 1949, that the remains of 1st Lt. William W. Read were believed to have been recovered and the dental records confirm the remains were Bill’s. His father challenged the letter since it stated he did not have any defects in his teeth. Arthur Read told them, in a letter, that Bill had had one major tooth defect and he also told them that they had lost his son’s dental records. The Quartermaster Corps reprocessed the remains to identify them. Two dentist stated that the teeth matched with the dental Records of Lt. William Read. A Lieutenant Colonel E. M. Brown visited his father and brought Bill’s file with him. Bill’s father on July 29, 1949, accepted the finding that the remains were his son’s remains. He requested that the remains be returned to the United States.

On Nov. 1, 1949, the Quartermaster Corps confirmed that Bill’s father wanted him buried at Arlington National Cemetery. A casket, with his remains, was put on the USAT Nelson Walker on Oct. 15, 1949, the day the ship sailed. The ship arrived in the US on Oct. 29th at San Francisco, and the remains were sent to Ft. Mason on Oct. 31st. From Ft. Mason his casket was sent to the Remains Distribution Center 1, Brooklyn Army Base, New York Port of Entry and arrived there on Nov. 9, 1945.

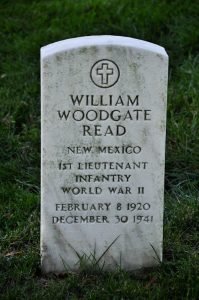

Bill’s casket and the caskets of twelve other men were sent, with a military escort, from New York to Washington D.C. on Train 21 on the Pennsylvania Railroad. His casket arrived in Washington about 2:40 in the afternoon on Dec. 19, 1949. 1st Lt. William W. Read was buried in Section 34, Grave 4703, at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia, on February 7, 1950.

There is one last story involving 1st Lt. William W. Read. After the men had been liberated at the end of the war, they sailed for home. One of the nurses caring for them on the hospital ship repeatedly approached the former POWs and asked them if anyone had known a 1st Lt. William W. Read. Sgt. Owen Sandmire, of A Company, heard from the other men that a nurse was asking about Lt. William Read, so he went looking for her. When Sandmire found her, the nurse explained that she was Lt. William Read’s fiancé and that they had intended to marry when he came home. Sandmire told the nurse the details of 1st Lt. William W. Read’s death.