Many of them were kids. Some were still in high school. Others had been in the National Guard for years. It was 1940 and the new men had joined the National Guard because a federal draft act had recently been passed, and they knew that it was just a matter of time before they would be drafted into the army. Having heard that the federal government was going to federalize National Guard units for a period of one year of military service, these men decided joining the National Guard would be a good way to fulfill their military obligation. Many believed that in a year, when the companies were released from federal service, they could begin planning their lives.

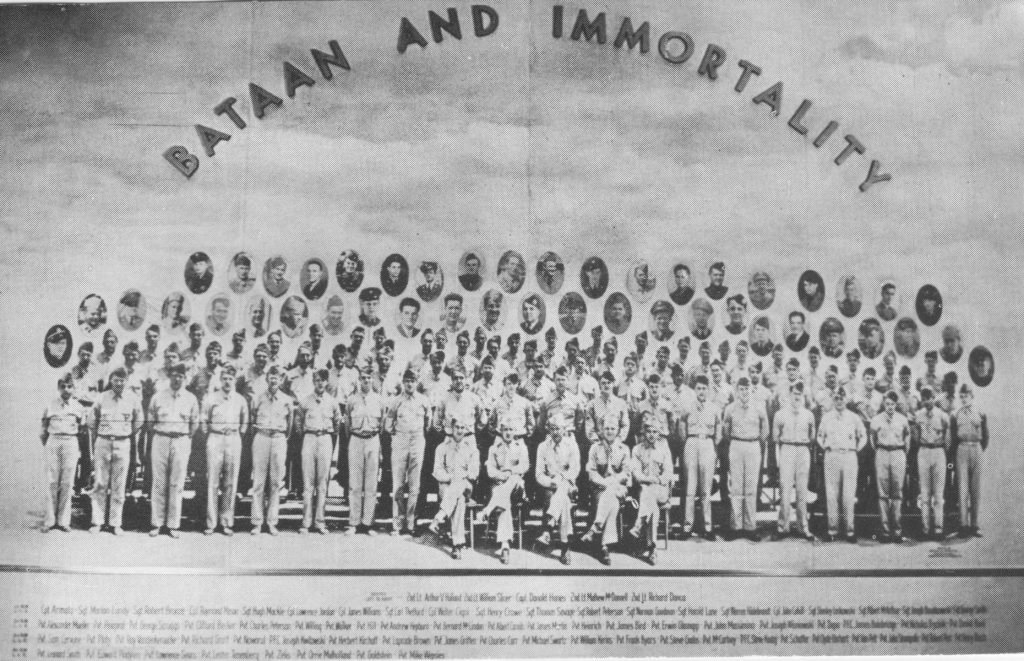

Company A came from Janesville, Wisconsin, Company B from Maywood, Illinois, Company C from Port Clinton, Ohio, and Company D from Harrodsburg, Kentucky. On November 25, 1940, they traveled to Fort Knox, Kentucky, where they came together to form the 192nd GHQ Light Tank Battalion. The battalion was what the U.S. Army termed, “an independent tank battalion.” They trained together and, at first, often fought each other. They came from farms, small towns, and the big city. Finally, they took pride in the fact that they were the 192nd Tank Battalion.

In January 1941, since none of the tank companies wanted to give up their tanks, Headquarters Company was formed by taking men from the four letter companies of the battalion. After this was done, the army attempted to fill the vacancies in the companies with men from the home states of each of the National Guard companies. During this time, the soldiers attended the various schools that they were assigned to as tank mechanics, radio operators, cooks, armourers, electricians, welders, and other jobs. The tank crews trained in their tanks, while the medics were trained by the battalion’s doctors.

After taking part in the Louisiana maneuvers in the late summer of 1941, on the side of a hill at Camp Polk, they learned that they were being sent overseas. So much for one year of military service. For two weeks they lived in tents and it seemed to rain constantly. Those 29 years old or older were given the chance to resign from federal service including the battalion’s commanding officer. Many of those who were left went home on leave to say their goodbyes.

Replacements were sought to fill the vacancies created by the resignations. Many of these men came from the 753rd Tank Battalion which “just happened” to have been sent to Camp Polk from Fort Benning, Georgia. While other men came from the 3rd Armor Division, also at Camp Polk, or the 32nd Armor Regiment stationed at Camp Beauregard, Louisiana. None of the soldiers, who remained or who were new to the battalion, had any idea what lay ahead of them.

Traveling west over different train routes, the companies of the 192nd Tank Battalion arrived in San Francisco and were ferried to Angel Island in San Francisco Bay. One soldier recalled thinking, as they passed Alcatraz Island, that they too were prisoners on an island. At night, they looked across the bay at the lights of San Francisco. For many, this was their last image of the United States. The men were given another physical by the battalion’s medical detachment, and those who had medical conditions were held back and scheduled to join the battalion at a later date. Other men were replaced by men who appeared to have been sent to the island as replacements.

Sailing from San Francisco for the Philippine Islands, they stopped at Hawaii. Many noticed that the climate there was one of preparation for war. Posters warned of unintentionally providing information to spies. Other posters asked that men volunteer for fire brigades. West of Hawaii, the ships sailed under complete blackout. One member of the battalion got into trouble for dropping an apple core into the ocean. An officer yelled at him that the apple core could reveal their location to the enemy. What enemy was he talking about? The United States wasn’t at war. Only after convincing the officer that apple cores didn’t float, did he get out of trouble. In another incident, an escort cruiser took off after a ship that was spotted in the distance and had failed to identify itself. One man recalled that the front of the ship came out of the water. As it turned out, the ship belonged to a neutral country. Two other intercepted ships were Japanese freighters hauling scrap metal to Japan.

Arriving in the Philippine Islands at Manila, there was no welcoming committee to meet them, and they were rushed to Ft. Stotsenburg and Clark Field. Upon arriving at Ft. Stotsenburg, they were greeted with chants of “suckers” from other American soldiers. Their dinner was a stew thrown into their mess kits. Some men needn’t even get that to eat. It was at this time that D Company was attached to, but not transferred to, the 194th Tank Battalion. Since their barracks were unfinished, they lived in tents. They spent this time learning about their M3 tanks which they received to replace their M2 tanks. For a little over two weeks they worked to prepare their tanks for the maneuvers they were expecting to take part in; What they were about to take part in was totally unexpected.

On December 6th, in the US but December 7th, in the Philippines, they loaded their tanks with ammunition for their tanks’ main guns and their machine guns. On Monday, December 8th, December 7th on the other side of the International Dateline, just ten hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, they lived through the attack on Clark Field. The attack wiped out the American Army Air Corps, and the first member of the battalion was killed during the attack.

At Lingayen Gulf on December 22, 1941, a platoon of B Company’s tanks engaged enemy tanks. This was the first time American tanks fought enemy tanks in World War II. Another soldier died during the engagement and four battalion members became Prisoners of War. A little under two weeks later, C Company’s tanks would engage and destroy a company of Japanese tanks.

For the next few weeks, the members of the battalion fell back toward the Bataan Peninsula with the other Filipino and American troops. The tank battalions repeatedly held their position so that the other units could withdraw before they fell back to the new defensive line. At Plaridel, the tankers fought a frantic battle against the Japanese to allow the southern forces to withdrawal into Bataan. They were asked to hold the position for six hours to allow most of the Filipino and American troops to cross the Pampanga River; they held the position for three days.

As they fell back, they were constantly strafed and shelled. Since they had no air force, no place was safe from enemy planes. The 192nd Tank Battalion was the last American military unit to enter the Bataan Peninsula just moments before the last bridge over the Pampanga River into the peninsula was blown up by the engineers. There, they would continue to fight without food, without adequate supplies, without medicine, and with only the hope of being reinforced. There was always talk that American ships had been seen off the coast of Bataan.

The belief that reinforcements were coming was also lost when they heard the Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, on the radios of their tanks. In his speech, he spoke of how some Americans had to be sacrificed if the war was to be won. The soldiers knew Stimson was speaking of them. It was at this time that many made the decision that they would rather fight to the death than surrender.

On April 8, 1942, General King sent his staff officers to meet with the Japanese for terms of surrender. One of the jeeps was driven by a member of the battalion. The white flags on the jeeps were extra bedding from A Company. At 6:45 in the morning, the order “CRASH” was given. Upon hearing it, most of the tankers destroyed their tanks and other equipment before surrendering to the Japanese. It was on the morning of April 9, 1942, that many of the members of the battalion became Prisoners of War. Having heard that the Japanese were looking for them, they stripped their uniforms of anything that indicated they were tankers.

Some of the soldiers wondered what people at home would think of them because of this. Others escaped to the Island of Corregidor to fight on for another month. Three joined the guerillas. Two of the three would be killed by the Japanese, while the surviving man spent the entire war as a guerilla fighting the Japanese. The rest made their way to Mariveles at the southern tip of Bataan, where they started what they simply called, “the March.” American newspapers would later call it the Bataan Death March.

The march was long and hot. The Japanese had not expected such a large number of prisoners and were not prepared to handle this number of prisoners. Most of the POWs, if not all, were sick. Many of the POWs went days without food or water on the march. Some of the members of the battalion died of exhaustion or were executed simply because they had dysentery and had tried to relieve themselves. As one member of the battalion said, “We were all sick. It was more of a trudge than a march.” The battalion members trudged their way for days attempting to reach San Fernando. It took some of them two weeks to complete the march. Often they marched at night. At times, they stumbled over the bodies of Filipinos and Americans who had died or been executed.

At San Fernando, they were first held in a bull pen before being sent to a train depot in 100 men detachments. Since there were 100 men in the detachments, the Japanese crammed them into small wooden boxcars used to haul sugarcane known as “Forty of Eights” since each car could hold forty men or eight horses. They were packed in so tightly that those who died remained standing. At Capas, they disembarked the cars and the bodies of the dead fell to the cars’ floors as they did so. The POWs walked the last few miles to Camp O’Donnell.

Camp O’Donnell was an unfinished Filipino Army base that the Japanese pressed into service as a prison camp. Any POW with Japanese items on him was executed. Disease and the lack of food and medicine took their toll on the weak. There was one water spigot for the entire camp and as many as 50 men died a day. The burial detachment worked nonstop to bury the dead. To escape the camp, members of the battalion went out on work details to rebuild what they had destroyed weeks earlier as they had retreated. Others worked recovering scrap metal that was sent to Japan.

When a new camp at Cabanatuan opened, the “healthier” POWs were sent there. It was in this new camp that they were joined by the battalion members who had escaped to Corregidor. Most of those POWs who remained at Camp O’Donnell died. For some battalion members, Cabanatuan was where they would spend the remainder of the war, while other battalion members were sent to satellite camps in other parts of the Philippines. Still, others were boarded onto cargo ships and sent to Japan or another occupied country.

As the war went on and American troops got closer to the Philippines, most of the members of the battalion, who still remained there, were sent to Manila for shipment to Japan. This was done to prevent them from being liberated. Many members of the battalion died in the holds of Japanese cargo ships. Some died from the heat, some passed out and suffocated, one was murdered by another American for his canteen. Most died when the ships they were on were torpedoed by American and British submarines. The reason this happened was that the Japanese refused to mark the ships with “red crosses” which indicated they were carrying Prisoners of War.

After the American armed forces landed in the Philippines, four of the battalion’s members were burned to death on Palawan Island, with other POWs, by the Japanese. They simply did not want the POWs to be liberated by the advancing American army. The luckier battalion members were freed when American Rangers liberated Cabanatuan on January 30, 1945. Some were freed when Bilibid Prison was liberated on February 4, 1945. They were the first to come home and tell their stories of life as Japanese POWs.

Those battalion members who had been sent to Japan, or another Japanese controlled country, were used as slave labor. They worked in factories, they worked in condemned coal mines, they worked in copper mines, they worked in steel and copper mills, they worked as stevedores loading and unloading ships, and they hauled hazardous chemicals. They worked for weeks without a day off and with very little food. What kept them going were the rumors and the planes. The bombings of Japanese cities became more frequent. American planes flew overhead both day and night. At night during an air raid, one member of the battalion recalled peeking out of the window of his barracks to watch the fires from the bombing. He thought they were beautiful.

One day, a member of the battalion watched an American bomber circle above the shipping docks where he was working. The plane dropped leaflets to the POWs working on the docks of the Japanese port. The leaflets indicated that the Americans knew where the prison camps were located. The POWs began to sense that it was just a matter of time before the war would be over. The only question they asked themselves was, “Would they be alive to see the end of the war?” They did not know that the Japanese command had issued an order that if American forces landed in Japan, all POWs would be executed.

Rumors began to fly that the war was over and that Japan had surrendered. Some of the POWs had heard the Japanese emperor on the radio. Others had witnessed a great explosion over Nagasaki. Even after being told by interpreters that Japan had surrendered, they did not believe that the war was over. It was only when the guards vanished, from the camps, that they knew the rumor might be true. This belief was confirmed when American B-29s appeared over the camps and began dropping food and clothing to the men in the camps.

Most of the surviving members of the battalion were returned to the Philippines to be “fattened up.” The United States government did not want them to be seen until they were healthier looking. Many of the surviving members of the battalion returned home, married, and raised families. They tried to get on with their lives. Some were successful at doing this while others never really recovered from their years as Japanese POWs. Of the 596 soldiers who left the United States in late October 1941, 325 had died. Some in combat, some were executed, but most died from disease or malnutrition while Japanese Prisoners of War. Many died in the holds of ships that were sunk by Allied submarines.

Today, all the surviving members of the 192nd Tank Battalion are gone, and those who chose to share their stories with us have since passed away. Often, doing this was a very painful experience. As one member of the B Company said to us over twenty-five years ago, “You’re asking me to tell you about something that I’ve spent the last fifty years trying to forget.”

It is our hope that this project keeps their story alive just a little longer.